Group Interview - Sketching a Succession

During their group exhibition Sketching a Succession at 35 North in Brighton for Photo Fringe 2020, Ezra Evans chatted with artists Anne Erhard, Eva Louisa Jonas and Cameron Williamson. Their conversation covered the common threads between their practices, how the exhibition came together and how they presented work in the space.

Ezra

Let’s start with a brief introduction to the show before we focus on the individual works.

Eva

The show explores our simultaneous realities, making work in different locations and then all echoing a similar appreciation and interest for rhythms, nature and I suppose, intuitively working. But also, the research and coming back and putting your ear to the ground and finding a strand. Looking at these different places, from three different perspectives, bringing it together then highlighting our response to the world, to chance, to order. Also gathering images, test prints, contact prints, diptychs together.

Anne

Definitely. In a way, we all look at history in a much wider sense. There is a lot of work looking at the relationship between place, land, landscape and history. Not just the history of the people within the place, but also the longer history of the land itself.

Cameron

That's what you meant with the ‘simultaneous realities at play in different times’ – things existing in varying feeds through history and what it means to take that photograph, it's all different timelines into one, visual form is what that phrase is touching upon.

Eva

There's a sentence at the end of our collective exhibition statement, in Anne and Cameron’s section it says "unfolding as something at once personal and universal". It's the sense of peripheral, intimate ideas of local, but also international; there's no specific geographical bearing. Although within elements of yours, Cameron, I know it's an exploration of Cornwall and there are symbols, monuments and other landmarks.

Cameron

That are distinct to the place.

Anne

Even though Cameron’s is more specific, we all still touch upon things that spanned several generations and look at ways history repeats itself.

Cameron

Yes, certain images of mine have similar metaphors, or do the same thing in a formal way, but they've been approached with very different subjects. Some are just rock formations; as old as everything, and then things from more recent human history and I chose various different metaphors to thread all of it together.

Eva

In a sense, the place that I came from in collaborating with you all is an appreciation of your work. Having followed both of you, on and off, for a couple of years, I just like your approach, which is quite a slow, attentive, and intuitive way of working.

Ezra

Let’s talk more about the individual works within the show. Were you all split up into sections on the walls, or was it created as one seamless exhibit?

Anne

Both in a way, each person's section works together as a unit.

Something we didn't think about consciously, but visitors have mentioned is that we didn't use any name tags. I think, in the end, it really helped the show as a whole become a unit.

Ezra

It’s interesting that you spoke about research, because how the images are arranged on the wall feels like a photo essay. I think the very subtle mid-tones and pensive black and white images throughout the show give it a dreamy feel. There's also a slight element of sculpture coming into play. There are things that want to be touched – from the cloth that, I think, is in your work Anne, to the stands for Eva’s books. Another really eye-catching part is the blue fillers in Cameron’s picture frame.

Cameron

When I was thinking about showing this work I had a museum in Helston in Cornwall in mind. I wanted to distill some sense of that small community museum and that's what was inspiring me when it came to displaying it. I've not really ever made a grid format with small pictures before. I've always been against it. I thought it would work in this instance, purely because I wanted to emulate what it feels like to be in that place. Again, with the blue and the wood, it's a little bit like those display cases. That’s one way of thinking about it.

Ezra

Am I right in thinking that's the only colour in the whole show? Everything else is black and white.

Eva

Yeah, we got crazy there!

Anne

Your frame is also interesting, because I have the cloth and Eva has the plinth with the book and the piece in the window. We all, without really meaning to, made a display with a slightly different focal point, and other images around it. Maybe that was another thing that, in the end, created a coherent display. We all had a really similar structure with one central thing that pulls you in, and all the other images clustered around it.

Eva

Within each of our sections, there are traces of wanting to emulate the contents of the image. Whether it's the flow in the fabrics that Anne’s made, or the frame I've made that pinches and holds the image. It acts as a focal point, it also feels like the show flows nicely. They're all separate images, or different bodies of work, but there's similar exploration, hopefully, bringing it to one comfortable conclusion or consensus.

Cameron

The materiality of how the work is displayed is a factor when making the work. It's not just an afterthought, it's part of the work. For example, with your work Eva, the way you've printed it and chosen to display it – it’s your way to refer to the book, but also play with what you wouldn't be able to do in a book. With the material and my choice with the frame, it's not an afterthought.

Ezra

There's definitely a parallel to be made with the interest in patterns. Within the images, there's a very distinctive amount of patterns and lines. Also, the way that it’s curated, I think in the way that your eyes are drawn through the images, but then also around the gallery space, then through Eva's books - It’s all very similar and for me, that really comes across when seeing the show.

Eva, would you like to talk about your images and how you went about making them, and the relationship between the works in the books and the works on the wall as well?

Eva

The images themselves are an edit that I've pulled out of the book to exhibit, I've worked backwards because, as a whole, it's been compiled for book format, rather than an exhibition and that's not something that I've done before. The images on the wall, they're not extensive of what might be shown or taken. We've actually been asked to do a show in Bristol of a similar format – to travel and take the exhibition to Bristol. I think in a way, it might change what images I choose to exhibit.

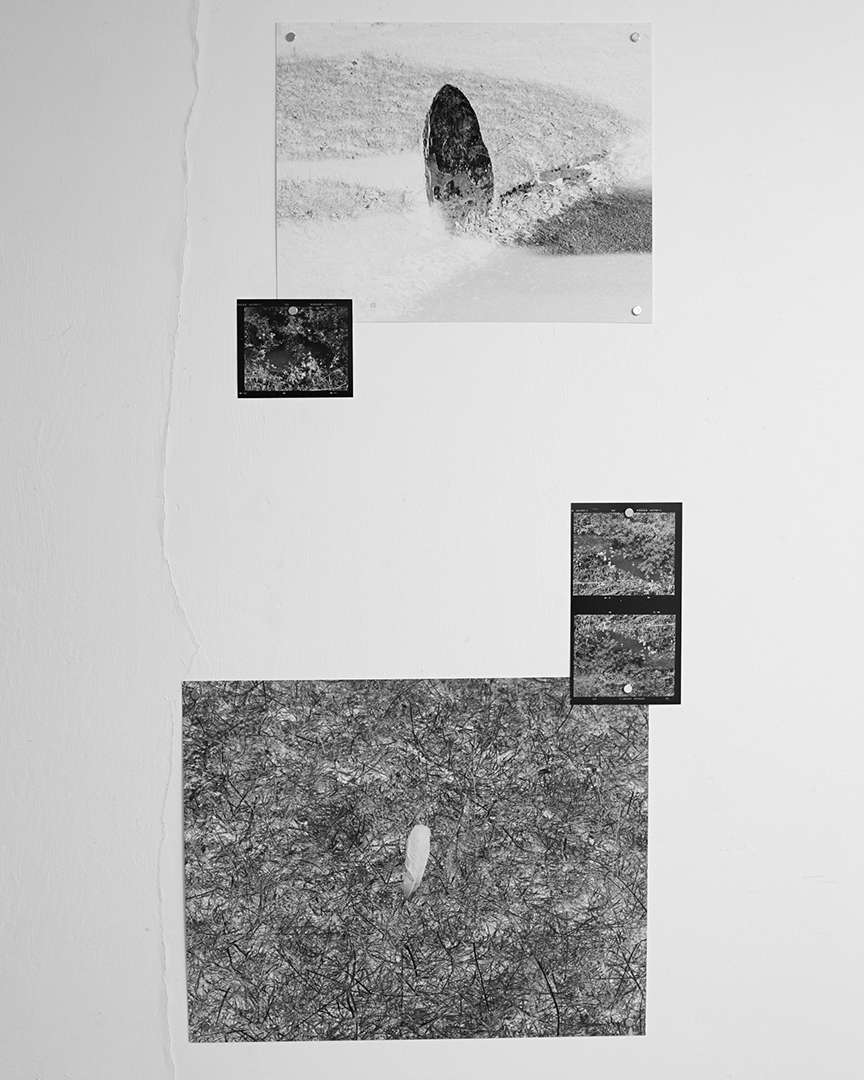

The work draws together two to three years of work, forms, assemblages, surfaces. It's a trace of my wanderings as a photographer, coming across different materials and gestures, some of them manipulated, some of them made and some of them already present. Then, coming back and finding associations and pairings and working quite intuitively to create a narrative of something that feels intimate and close, but also peripheral with no geographical bearing in itself. The title of my section of the work and of the book is Let’s Sketch the Lay of the Land. That’s drawn from the title of the show ‘sketching a succession’. It's this idea of trying to find some kind of conclusion but in a sense, not really needing to, I think that's my working process and practice.

The image in the window, pinched in the frame, is to emulate the sense of tension and malleability echoed throughout the book, humans and nature, but not wanting to explore that, or make reference to that in a big way. Then there's the book pressed in the frame as if it's an object on the plinth. Then aesthetic considerations like using the same wood or finish, and wanting to emulate this sculptural exploration and material exploration that some of the images have too. It's been made in a book format where you turn the page and there's a whole vast edit of 50/60 images, and then having to extrapolate that and take it out. I only had about ten images in the show. I think for me the work and exhibition format is something that still feels very raw and is something that I really want to build on. Hopefully, with the show in Bristol, it's something that we can all do to build on our ideas and explorations collectively.

Ezra

The smaller of the two publications you’ve shown includes photos of structures you've made yourself. There’s a slight tension between natural forms and structures, but also the man-made – whether those be ancient things made with materials like stones or sticks or the ones you've constructed in the little booklet. Could you talk a little more about those structures?

Eva

That work isn't in the main book because I made it more recently, but I felt it was important to include it because, just as the images in the book are documents of my immediate environments, or my wonderings, the little structures I made were in response to having to stay in more domestic environments and trying to understand what the next move might be. l don't want to say it's a lockdown project, but it kind of is. It was a playful collaboration with me and my family when I came home for a short while. To make and assemble these wooden blocks and think about the scale, form, figure and movement and make a mini maquette version of what we can and can't do. Although those images aren't in the book, it felt in tune with that working method of exploring materials to mimic human gesture without it being actual bodily form.

Ezra

I love the little stand the booklet was on. There is a bit of mirroring between the shapes in the book and the stand. Cameron, could you elaborate on your works in the show?

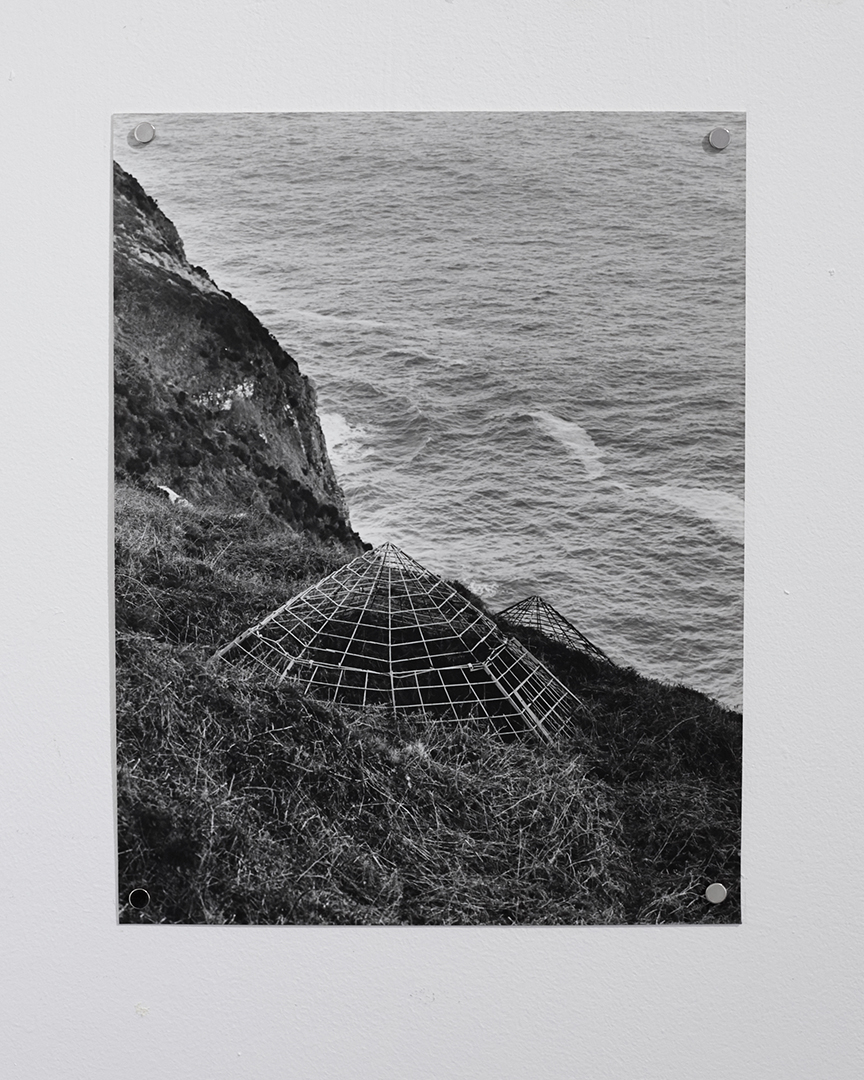

Cameron

On a recognizable level, there's an exploration of different forms in a particular region of Cornwall, the Lizard Peninsula, which uses my mum’s ancestry as a touchstone to explore different historical impacts on the landscape. Whether that's directly through the examples of mining that you see or stuff that's a lot older that’s also manmade, then mixing that with things that are natural. There’s an ambiguity between what is manmade and what is natural, between how old they are and how long these processes have been going on. There's also a literal metaphor that I had joined to the project at the same time as I started, it's reflected in the forms you see. A lot of very triangular forms with either a light space in the centre, or a dark space, those in the mineshaft, the tops and things. Basically, there's a space created there visually.

An aspect of the work is thinking about the word ‘hold’, as in, ‘bringing together into bundles’ or, to create a ‘hold’ in the landscape or a space of existence for a person or a group of people. Talking about the physical act on a landscape, for example, moving earth and creating these spaces underground. I'm really thinking in a very abstract way about what they were doing. Creating space underground in the landscape and altering it in such a strong way. Intermingling different timelines evident in the landscape, whether made in the last 200 years or whether it's much older. There are different time-frames. This is something that's probably quite relevant to all of our work. It's not rooted in history. It's not placed in a time in a strict sense. It’s certainly something I try to leave out as much as possible. I try to avoid placing the work in a specific time frame.

Anne

I think that also brings us back to the theme of the personal and the universal, I do think we’re all quite specific in what we do. Cameron, maybe you don't chain it to a particular time, but you do create a very specific narrative and very specific visual scene-setting.

Cameron

Yes, there are restrictions.

Anne

Someone told me when you make work that's personal, it's a good idea to make it really personal, because that's what will make it universally appealing and understandable. I do think that, even though we don't explicitly communicate it, we all do it. We each have a very deeply personal approach and language.

Ezra

I think that comes across. The use of black and white in the images is interesting, because you've created something that's really soft and quite touching, personal and almost, dare I say, a little poetic in a medium where you normally get very harsh contrasting tones. You have all used it in a very subtle and dreamlike manner.

Anne, would you like to talk us through your pieces in the exhibition?

Anne

It’s very much a work in progress, as all of our work is, in one way or another. I am studying for a part-time MA at Westminster. I finished my first year in the summer and I was supposed to be starting my second year now, but it's been pushed back a little bit. I started the work as part of my first year, so last term. It’s all work I've started making since my father passed away about a year and a half ago. It's a wild pool of images that I've drawn from lots of different sources. There are some images in there that I actually took before he passed away. It was the last time I saw him and also the last trips that we made. There’re images that I've taken since then and also images I've drawn out of the family archive, images I took in Germany, images I took in the UK.

There's a very disparate pile of stuff that I'm really slowly sifting through. Seeing how different pieces might puzzle together. I showed some of the images in a work-in-progress exhibition back in February 2020 that we had at uni. I also showed some colour work. The black and white contact sheets were in there already and Cameron had been in the same place, in that, there were some colour images too. We both reached that point where we were curious about what it might look like without them. That's something that I've done multiple times before, I've started a project in both colour and black and white and then the final thing ends up being black and white. We still try it, but then always veer towards the other one, so I decided that along the way.

I wanted to make something different from what I showed in February because I've done a lot more thinking since then – I've taken new images and thought about some images in a different way, it just felt like it was the right thing to do for the whole show to work.

Ezra

You’re showing some texts in the show as well. I think you all work with texts a little bit? Can you talk about the importance of text in relation to the photographic image and of exhibiting them together?

Eva

Although I didn't have text on the wall, like Anne did, I have written text in the book. The text in the book is just as important as the images, but you don't really see the text if you flick through the whole book as it’s at the back. Having a formal text that was arranged in a very traditional way felt like a bit of a betrayal of the book design, it just didn't feel like it fitted very well. The text collage towards the back of the book felt like it behaved like the images. In the way that it moved and collated with a lot of different phrases that are in tune with working methods and forms of inspiration. The title is also placed a bit like the text collage, it jumps across the page.

I really enjoyed the text, having it dancing like that on the page, it hints at what to expect, the different scale and sizes you're going to come across in the book. Also, the thin grammage of the paper allows a shadow of images between the pages, creating a dialogue between partially visible images. So there’s an interplay of scales and sizes and then being able to see them through the thin paper. I’m still comfortable with the text being in the back of the book, but I hadn’t presented it in an exhibition before.

Anne

For me, it's not so much about a distinction between photography and text, I work with material. That could be my photographs, or from my family archive, or from anywhere else, or a text I’ve written, or taken from an archive, or it might be a typewritten page that I found somewhere – or extending that to an object, like the text I had in the Fringe exhibition.

The text on the wall is an excerpt from a diary that my father kept and I found. Previously, I've used pieces of found text, letters from family members and from previous projects. I see it as another material that I've collected to weave into the project. I also showed a text that I had written. I feel I'm trying to employ the same process across different materials. My intentions in the text piece with my father's diary were the same as with the images that I was using. I was thinking a lot about ideas of repetition (this oscillating timeline), simultaneous events, and how a written description of something would interact with the image.

Ezra

Tell us about the sheet of fabric coming down over some of the images and the reason behind that?

Anne

Cameron and I managed a trip to Scotland, just before lockdown proper, back in March 2020. We had travelled around taking some new images (none of those images are in the exhibition)

I'm looking for different objects, or different things I can employ within the structure of the project to signify certain things for me. The same goes for literature about loss and grief and death – the idea of the veil is a very prominent notion. In terms of one side and the other, like the passing through the veil. It was a very present idea in people's thoughts. I held on to that image for a while and I thought it could be something. I can't remember how, but one day I thought what if I try to print on fabric? and it turned into this curtain.

Ezra

The exhibition title Sketching a Succession - I'm aware Anne has another project by the same name. Let’s talk about the naming of the show and what it means? There are other mentions of sketching and drawing in Eva's work, can you touch on this idea of interpretation as alluded to by the title and how that runs through the work?

Cameron

I actually suggested it to Anne. We were trying to think of a title, and I asked ‘how do you feel about reusing that?’ Because it was a short mid-term project originally.

Anne

It was from my BA. It's one of those that I still half-see as a project, but on the other hand, I don’t.

Cameron

It's one of those things where you test ideas out then you make a more contextual piece afterwards. I was drawn to us stealing the name because sketching also forms a part of the title for Eva’s work. Immediately that's a really nice way of tying it in. Then succession as a word, I feel like it relates in different ways to all of our practices. We didn't have long to think of a name so I was like, Oh, this actually really works!

Anne

I think the longer it's been there, the better it's worked. Especially now that the show is up and the way it’s been installed. Now we’re talking about it more, we’re realising all of our works are still in some stage of being made. The title also hints at this idea of processes.

Cameron

Processes that are happening in certain places as well.

Eva

It was just something that flowed really nicely.

Ezra

Can you each elaborate on your working processes? The relationship between research and creation, and going out and performing, or capturing these images?

Anne

I've always thought this is a twofold thing. On the one hand, my understanding of what constitutes research is not so tight in that way. It can be going to small, crusty, local museums and immersing yourself in spaces and situations, or digging out boxes from a family member's attic and rifling through old documents. That kind of research is very tied into your life, it's a way of learning about things. It's less about an institutional idea of research.

Cameron

I always find if you've got a book on your shelf, you’ll always end up reading it at the right time. They come into your life and when they’re relevant you'll find them. Which feeds into how you start seeing other things and how you encounter other artists’ work, or other books, fiction or otherwise.

Eva

I thought you said very succinctly Anne, about my approach to research as well. I have a mental disparity between what I see as being highlighted as a formal approach to research and it not being akin to my type of retracing. It just comes to you at the right time, a book, or a phrase, or a piece of text, or an image, or something even more random.

Anne

I also agree with Cameron that theoretical research, or the reading part of it and the image-making part, don’t have to come one before the other. I don’t feel it works in that way, where you start by reading and then you take the photos, I think it's a symbiotic relationship. Once you start going out and taking pictures they give you a clearer idea of what things you need to read, and then both can go forward at the same time.

Cameron

One more distinct aspect of my work is that much of it was made over a couple of years and a lot by driving. I've always started with a basic site, or something that takes your interests in, either in an article somewhere, or something like a really hidden tourist information website. You've got research-based glasses on and you're really attuned to certain things that would otherwise just be the most random collection of objects on the dustiest website ever. It suddenly piques your interest, and you start there, and that leads you on to the next thing.

I know from my project, the second time I went, I used Ordnance Survey maps a lot. I tried to put myself in a position where the work might happen. I might be somewhere at the right time where something might come of it. Then there were sites that are specific to the ancestral side of things. I would try to generate a flow where you keep driving and keep going to the next place, keep walking, going back to places the next day, checking the weather, trying to sustain a flow. I've done that in the past, using movement to sustain the making of work.

Ezra

You're putting yourself in the right place for the images to happen, but maybe not necessarily planning the images as such.

Cameron

Yeah.

Anne

Something Cameron and I have also talked about, is that towards the end of our BA and more recently, a lot of what we take from reading, almost all of it comes from fiction. I think, all of the most mind-blowing things we've read, or we've somehow incorporated into project work, or things that have changed our understanding of how we make work, generally have all come from novels.

Ezra

What novels are they?

Anne

Definitely László Krasznahorkai. He's Hungarian. They’re incredible, all the sentences are ten pages long. It's so good!

Cameron

It's really good episodic work.

Anne

The book is called Seiobo There Below and it's relevant to everything we've been talking about in terms of the show, because it's a novel but each chapter is a completely different story, with completely different characters, in a different time, and a different country. It's almost like each one is the same story over and over again but they’re super interlinked.

Ezra

There's a shared narrative, but a different story?

Anne

Yeah. I remember that whole thing. It really blew my mind because I thought this is what I've been trying to do with images and here is someone who has done that so amazingly in a novel. I guess it also goes back to that idea of text as another medium or material.

Eva

In my relationship with research – finishing my final major for uni last year and the documentation that I used to gain accreditation by ‘ticking the box’ of research. I reflect on the images that have been made for a separate project, but then have been brought together in the book and the exhibition. I found it jarring that, although I was reading things I felt were at the core of my exploration, it actually made me feel I had to make a statement or have something bigger to say. There was a lot of ecology in and around spiritual equality and environmentalism and Michelle Serre's The Natural Contract and that sense of man and nature. It's interesting that thinking about my relationship to research and having read a lot of the content and trying to visualise it – it swayed me in a different direction. It felt like I had to have something really important to say, shift, or change. I think a lot of people can say that when there's a lot of exploration of nature. There are so many different strands, around colonialism, and climate breakdown and the international taking and shifting of flora and fauna. I didn't specifically know where to put that.

I think that's actually emulated in the collating of images in the book, this idea of sketching the lay of the land and finding out, but not coming to any specific conclusion – not that everything is as it should be. There is obviously room for a shift and change in our approach as humans.

Ezra

One of the interesting things about the work is how it makes you think about the history of human intervention on the land. There are pictures of trees and hillsides and stuff and you think well they have these natural patterns and these natural aspects but if you think back hundreds or thousands of years or even 50, 40 years, it was probably a forest planted by people, or fields ploughed by people.

Do your projects have a start and an end? Is it that defined to you? Or, is your practice more of a continuing development and flowing of work?

Cameron

It comes in waves, those peaks are the projects. I have so much stuff just kicking around, groups of images that work as pairs, or as fours. I started re-doing my website in lockdown. There are so many pairings and so many things drawn from different years and stuff that all comes together. I don't really say that I make work solely in a project sense. I don't take pictures in London that often, but otherwise I sustain making images and stuff that exists without a more direct context.

Anne

I do work in defined projects, but in the sense of working very slowly, so each project is at least two years until it's finished. I do have a very strong sense of how those projects are interlinked, for example, the work in the exhibition is, to me, a third part of what's currently a trilogy – maybe it will have other parts later. In the two bigger projects that proceed it and then this one, I can see a clear succession. In this project and the previous ones, there's always one little thing that directly creates the next one. It carries on like that. They are very big separate things, but at the same time, they're borne out of each other.

Eva

I think with the collation of the book being at the core of this work. I feel my memory is just the book now. It's been such a great focus for my practice. There are definitely lots of different images with a similar strand that I've separated for the purpose of accreditation in uni, but something I'm still learning and developing now, is trying to understand what is a much longer, more intuitive way of working, and then what’s isolated from that as a separate body of work.

Ezra

How did the show come about? What was it like working with everyone?

It's interesting to hear you talk about the work because, although there are distinct differences, I think the collective body of work you've exhibited merges together nicely. When viewing it there were no distinct boundaries between one person's work and the next.

Cameron

It was good to show the work the way we did – everyone coming from their own, very distinctive way of working. I think how it worked out, how people talked to us about it and the way the show sat as a unit, sets the scene to try something else in the future. Also, depending on what stage everyone is with work, it’s good to know it will gel together, whatever stage you're at. It doesn't need to have a distinction between your completed project and something that's more a work in progress. It all fits together quite well. I thought that was something interesting that came out of the discussion around the way the work fits together.

Anne

I think that's where exhibitions are really exciting because even when you have a piece of work that's finished, or you have a project that's finished and you're not going to take any more images, you still have an infinite possibility of exhibiting again in different ways. I think for all of us, the material aspect of the display is super important for the work. It's really exciting to keep experimenting with that and to be able to keep the project physically changing in that way.

Eva

I think it was a really great combination of things, in that we all managed to keep our production costs low. Also, we had a really great relationship with the owners of the gallery space – so we weren’t charged a fee. There was a sense of cohesion and having to fully realise the exhibition statement and then putting it up in a digital form on the Photo Fringe website. I think it was that thing of actually putting something up and presenting it, then the flow and intuitiveness of doing that and getting it out of your head. And it's like, okay, this can build, this can grow, this is really exciting!

Anne

We intended to do it as a group show, and we had a good idea of what each of our works were beforehand. When Eva approached us to do it, we thought immediately, it sounded good.

All our work is similar, but I also get the feeling, from talking to visitors, that we have somehow managed to turn it into more than we thought it would be. Not that we didn't think it would work. I think as soon as we put it up, or as soon as we had a better idea of how we were going to curate the show, physically seeing it there all together, almost effortlessly it gelled into a unit.

Not having the name tags and the positioning of the work created a flow. It's super interesting to carry on exploring that, also because that wasn't really our intention to be or form a collective, but we had that conversation later with people who came to see the show and amongst ourselves. Accidentally, we've made something that's so intertwined or just fits together in such a way that it would be really interesting to see how it might look a little bit further down the line.

Cameron

Also having confidence in that, because you've done it once before.

Ezra

I think something touched on there is how important the process of having an exhibition is to finalising work so you can move on from it, or to turn over a new chapter. In that sense, producing work is also a method of research, production and review. The live exhibition space is such an important part of that. It is strange, so many people have been unable to do that for such a long time and unable to finalise ideas or to properly understand an idea. It's so hard to know your opinion on a print or to be able to understand a print until you have it on the wall.

You have it for months and months and then continuously look at it and finally start to understand it. You mentioned earlier that you only had a really short timescale to put the show together. How long was that?

Eva

I think a lot of it was with the backdrop of Covid regulations as well, and not knowing when people were able to come in and all of the laws changing so often, etc. I think that was quite a big backdrop. I think working in these specific areas, where less stuff was happening during lockdown, then suddenly, it was everything at the same time. I know that you, Anne and Cameron, were both really busy again. To meet the Photo Fringe deadline, there were conversations and it came together. Then, being able to meet and discuss further was great.

Anne

We had been talking about the show since late February. But then there was a large time gap, we weren't sure whether we would actually be able to physically have it, then everything went up in the air until very shortly beforehand.

The idea of the exhibition was always there, but then how it ultimately came together and then when we knew we better submit and register, because it’s actually going to happen now after we half thought it wouldn't. After that, the whole timeline got a little bit more mashed up.

Eva

I couldn't quite believe that we were actually open on that first weekend. It was on the back of the tier-two London restrictions. It was surreal in a way – having friends who cancelled their in-venue exhibitions because of the restrictions. There was a lot of cost and outlay involved in their shows, so that was quite a large practical decision.

It’s interesting the relationship between having this digital space to curate with a very simple design and wanting to emulate something that we hadn't physically put up yet. On the digital exhibition, there's no trace of this material exploration that we'd brought together, although those conversations were going on a little after the digital exhibition deadline. There was no way that we could present that digitally, but I think it's a really important way that someone could access the work. There is an element of ‘units’ and our own separate works coming together digitally. It was an initial coming together for this exhibition statement deadline, then the digital exhibition. Then, when making it physically, it was really nice to be together and chat about it, then finalise it.

Anne

It’s interesting – like you say, we ended up installing the show without that much of a plan beforehand because we felt the space was quite small. It ended up being quite a spontaneous thing. In a way, it feels like we've gone through lots of different stages – pulling it together for that digital show and finalising the statement and then having that in our minds. When it came time to physically put it up, it was really helpful to just move closer to the final thing.

Ezra

It’s interesting how all aspects of the process inform each other. It seems especially hard to curate a show, try and trace narratives through image arrangement and space on a gallery wall before putting up the show, unless you're making little maquettes. To do it on a computer screen is almost impossible. As you were saying, everything from the research and the curating of books and pulling images out of archives – it all informs the final display. We are quite lucky as it really seems that, in terms of smaller exhibitions, there's not really all that much that is able to happen outside of Photo Fringe. It was definitely scary when we were coming up to the first of October. It seemed like the country was all going back into lockdown. What brought you guys together? Was it all from being on the BA together?

Eva

No, actually.

Cameron

Eva's the orchestrator.

Eva

Very simply, I came across Anne's work on Instagram, it really resonated with me. We didn't study together, and Cameron studied at LCC. I just graduated from Brighton. I think in my second year, me and my friend went to Berlin. And I remember that Anne lived in Berlin, so I messaged her and we caught up. She gave us some great suggestions for exhibitions and kept in touch on and off since then, but we hadn't really seen each other since. We saw each other at Free Range, didn't we?

Anne

I think so.

Eva

And then just a lot of overlaps, I think.

Ezra

It shows that you had a vision, an idea of how everything would come together. It's not just a jumble of parts that ended up being lumped together in university.

Cameron

Yeah, writing the text really helped us to do that. It really cemented the idea that the works relate and that we're doing something helpful for ourselves as well as for our own practices.

Ezra

So Eva, you graduated last year, and Anne, you're studying for your MA at the moment?

Anne

Yeah, and I graduated from LCC in 2016.

Cameron

I was the year after.

Ezra

It’s interesting how the process of creating an exhibition and the process of working through ideas and imagery with other people, is such a prominent and profound experience to lose when you actually step away from the university bubble. Then you're in the real world and you think Oh, well, I'm going to continue as I am. But it can often drop away without the involvement of other people and exhibitions, which often help you to develop.

Anne

It's become very apparent this year – how lucky we all feel that we were able to do it. It really shows you how much changes when you physically show work. We had an idea of what it was going to be beforehand, and then we did it and thought it was going to work. And then it really worked.