Interview with Heather Agyepong - Wish You Were Here

Pelumi Odubanjo, one of the three selected Photo Fringe 2020 Trainee Curators, interviewed Heather Agyepong about the motivations and processes for this new work.

What kind of images can we create when we take the archive into our own hands? What do we capture when we turn the camera on ourselves? Who is being exposed, and who is in control? When it comes to the work of Heather Agyepong, it’s all about the dynamics of self-exposure and self-dramatisation. The dynamics of confrontation: between photographer and subject, image and spectator. These are the pillars of Agyepong’s practice, where the photographic space becomes a theatre of her own. Agyepong inhabits the space of witness, sometimes collaborator, sometimes both in front of and behind the camera.

When confronted with the camera, be it a mugshot, passport photo or selfie – we are all performing. If not for ourselves or other people, then for the camera. 'Wish You Were Here' unites the exterior and the interior, drawing from collected material and ambiguity, with a contemporary twist which lends itself to a historical contemplation of body, time and place.

I sat down with Heather towards the end of last year via Zoom, where we discussed the body, performing for an audience, and art practice as a form of healing and therapy.

Pelumi- Could you tell me how you first conceived the idea for 'Wish You Were Here', which was a part of the Photo Fringe 2020 Festival?

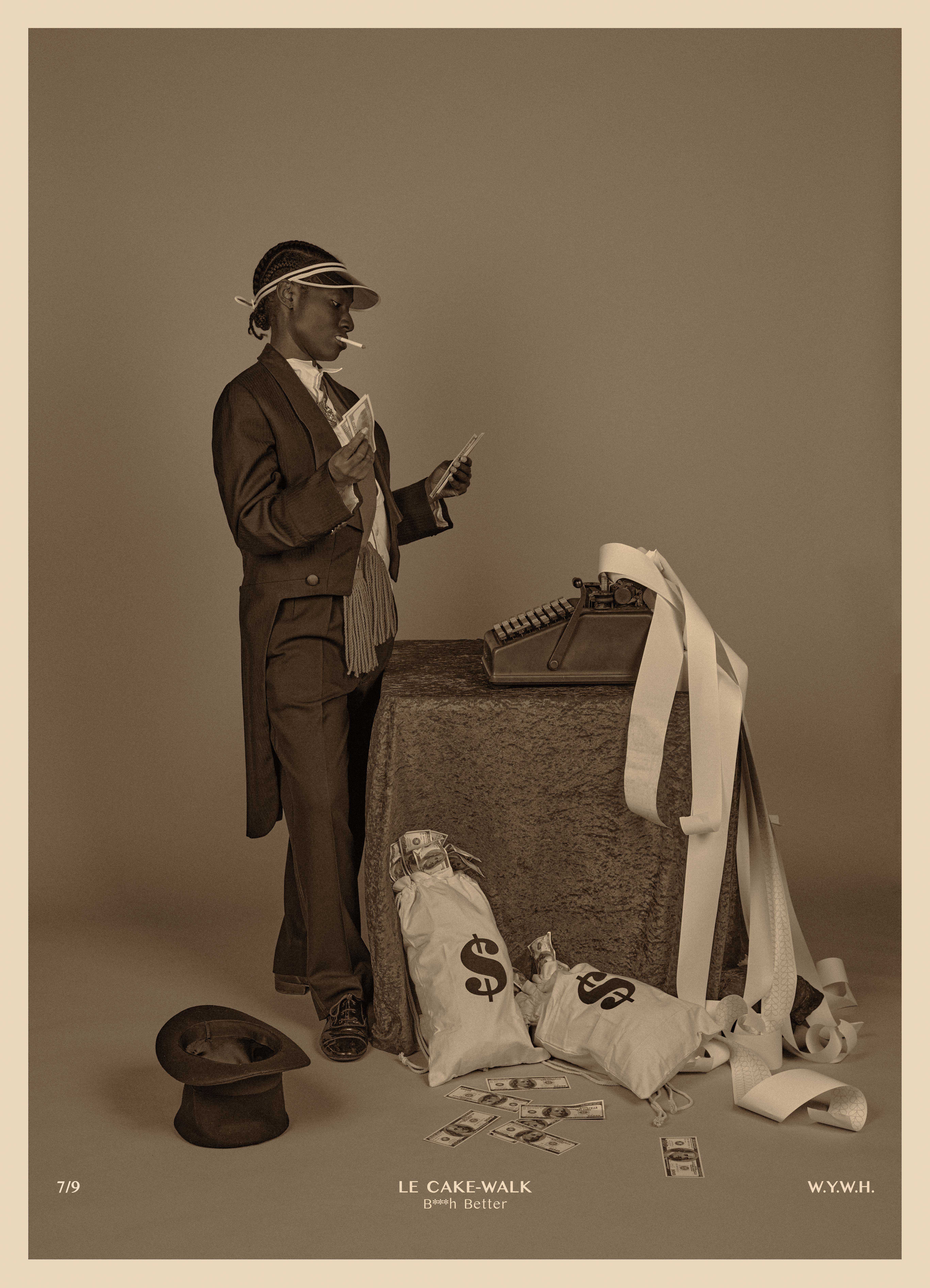

Heather- I was originally commissioned by James Hyman Gallery to create a piece of work, and a few weeks before, I discovered what a Cakewalk was. I found that dance move to be really subversive and interesting. If people don’t know, African American enslaved people mocked white society and created the dance, then after emancipation, they started performing such dances in non-conformative spaces, and whoever was the best dancer was awarded the cake, so it was called the Cakewalk. That really interests me, but James Hyman brought out other postcards of Cakewalk dancers as the Cakewalk was really popular in the early twentieth century, and asked if I could do anything with it and I said, ‘I was just thinking about the Cakewalk!’. It was really quite odd, how we were in tune with each other. So yeah, I saw the postcards, that was the first response of something kind of visual to the Cakewalk.

P- Can you elaborate on the significance of the postcard aesthetic for this work? Does it extend perhaps to a material history?

H- Initially, it was a response. The images of the postcards vary. As time went on, the Cakewalk dances became more racist and grotesque. Like, animals were doing the Cakewalk, and darker skin images with red lips. I wondered, how could I reappropriate that image to speak to my community and other marginalised communities? Initially it was about agency and inserting myself in the image, but then it also became about the women I was recreating, or was inspired by, like Aida Overtone Walker, who was very outspoken about what it meant to be a black woman, and talking about these kinds of limited embodiments of black womanhood on stage. At the time I felt totally opposite. I found it very difficult to navigate this as an artist, and I felt I needed a source of strength. The postcard idea became not just about geographical locality. It was as if Aida was talking to me from the past. So, the idea of 'Wish You Were Here' had multiple meanings. Also, I wanted to send these postcards to friends. Some of these images speak to ideas around financial instability, some of them about being bolder within your community, so they act as greeting cards given to communicate and to give a sense of uplift and encouragement.

P- And have they been used as postcards yet?

H- They will. We’re planning this for the exhibition that was supposed to happen a while ago, which has been postponed and postponed, so hopefully soon at the Arnolfini in Bristol.

P- The interplay between performance and the body is clearly of importance to your work. Why did you decide to articulate histories like that of the Cakewalk in such a way? For example, through self-portraiture, you've tapped into a re-enactment of Victorian women.

H- There have been so many educational gaps. People often talk about this, but these are not just educational gaps of ‘black British history’, or contributions, but of mere existence. When I was first introduced to the archive, it caused such a massive shift in me. It made me feel incredibly grounded knowing there were people behind me. I think before, this black British experience felt very new. My parents came from Ghana. I didn’t have any people to relate to, but knowing there’s a history of people behind me, it shifted how I see myself. I feel more whole. This idea of the archive, makes me want to pay homage to these people, because if it wasn’t for what they did, I wouldn’t be where I was. So, there is always a looking back. I feel it’s quite similar to therapy. All of my work has to do with mental health. You always have to look back to understand where you are now. So, I’m trying to mirror that context in how I use my art for looking back, and what I can learn from that to bring forward now. It’s probably always going to be in my work which is slowly becoming more conceptual, so less about recreating women, but it could be historical objects, something from the past that I feel is charged with secrets that I need to figure out.

P- As mentioned, much of your photography is about performance and the body, with your body being centred to the frame. Was this an easy decision to make?

H- No (laughs) I actually had no interest in doing photography whatsoever. I’m actually an actor. I’ve always been an actor. And then, mental health stuff started happening, so photography became a therapeutic tool whilst I was trying to figure out what was going on in my head with the images I was taking. A lot of them were about how I saw myself as a woman, as a black person, as an African. All of these ’issues’ around my identity were revealed in the images I was taking. My first ‘real’ project was when I went to Ghana. It was about representation and the responsibility of photographers, but then I thought ‘I don’t want to be very general, I want to talk about me’. The reason I picked up a camera was to understand myself, so I just thought, ‘let me forget all the b-s, let me put myself in the image’. The work is a performance, but also tinged with reality because this reimagination is all about my actual life, so within those images I’m making in 'Wish You Were Here', they are all about something that’s actually happened to me, whether it be about trauma, about financial instability, or, the burden of community, where sometimes you really want to help your community, but you don’t want to silence yourself. All of those frames enable me to have a deeper understanding of myself and the issues that happened. I don’t think I could make any work without it if I’m honest. From all of the projects, I want to get something out of it. I want to understand myself better, genuinely. Not just to make a pretty image on the wall. I want to really have some catharsis from the work, so that it feels essential.

P- How is the work made?

H- My projects take so long to make (laughs). They take me a day to shoot. They take so long to make firstly because I’m researching the person I’m trying to represent, but I’m also making a personal excavation with either a health professional, or, I’m writing, or I’m journaling. I’m really thinking about, "what do I want to say as Heather? What does the object or the character want to say as themselves?" I’m just reading loads about that person. It probably takes about six months of reading, because I often find that the ideas of the images will just pop up in my head. I’ll read, read, read, not even about making the image, but about the history and the context of myself and that person, then the idea of an image will come and then I’ll say , ‘okay!’.

The population of props probably comes after. When I made my first self-portraiture series, Too Many Blackamoores, the props were directly related to a traumatic memory, but now the props in 'Wish You Were Here' are quite emblematic of something that happened. I don’t want to be careless in the props that I’m using. They always have some kind of history behind them, or, another story that’s happening within the image. And then making the work takes a day. It’s quite intense. Often because it is a reimagination work, but it’s all based in reality. I’m saying words and sentences over and over again to myself in my head to be back in that moment. There are journals, trigger images, all because I want to be emotionally within it. Usually I work with brilliant assistants too, so when I’m ready to shoot, I say ‘go'. But the conception of the work is all mine. I’ve also found, when I try to take the images by myself, the work is actually quite heavy! It’s not really safe (laughs), it’s quite incredible! Or, I’ve found that I end up performing when I’m by myself, and it ends up being untrue, which is kind of interesting. There’s something about having witnesses around. It gives me the freedom to dip in, which is quite off. You’d think it’s the other way around!

P- Do you think it’s the other way around because you are an actor, and because you are so used to performing for people? Do you naturally find it easier when performing in front of an audience?

H- Actually, no. I think it’s the total opposite. For example, its different when I'm playing characters in my acting career because its way more about collaboration which I love but my visual art work is really centred around my own personal gaze. I find it very different. There’s an expectation. There’s something about making a visual art piece, something about saying ‘You are going to witness this. This is happening and this is real.’ There is…not entitlement…but a feeling, or perhaps strength in that. By myself it feels this is too important for people not to see, because this is really happening to me. When I’m playing a character, there’s an expectation, there’s all this other stuff. It’s not just you. There’s always someone else when filming.

P- How did your relationship to photography begin? Do you refer to yourself as a photographer?

H- I definitely don’t call myself a photographer. Definitely not. I always call myself a visual artist, because the tech stuff, I have little to no interest in. As long as it’s sharp focus, I can zhoosh it up later (laughs). Also, I know people who are actual photographers, and I don’t want to be cheeky. When I was 19, I went on the Jessops website and bought a camera. Like I said before, my mental health was not in a good way, so I just bought a camera. But looking back, I think It was because I wanted to get out of this internal chatter, and just focus on something outside of myself. It was definitely a therapeutic thing. I had to say, ‘Heather, you need to look after yourself. You need to focus on something’. I couldn’t focus on my work because it was in the same space as having all of these thoughts. I just thought, I need to take images. Then the images I was taking, I was taking pictures of black women laughing, ‘black joy’- I guess that’s what you’d call it now. I was taking pictures of homeless people in really rich areas. So, I was talking about class, and stuff that was going on with me in those images. They were all about me really and I was like ‘ugh, what is all of this?’.

Then I thought about how images, and how visual culture impacts mental health. That whole thing of growing up and having that sense of embarrassment of being African. It wasn’t about my experiences on the continent, it was about the images I was seeing. I think visual culture has a very detrimental effect on marginalised communities. Because if the dominant culture is having other people in control of our narrative, whether you like it or not, it’s going to impact you. Whether you fight against it and you live your life trying to fight that, or you totally internalise that and it impacts how you see yourself. I wanted to talk about what that was. Let’s not pretend photography of photographers don’t have an impact on us. They definitely do.

P- What are the cultural questions that were relevant for you to deal with in your work, and do you see these developing as your practice emerges?

H- There’s wanting to serve your community and wanting to serve yourself. I think when you’re quite specific in what you do, you’re adding to the collection and the nuanced voices of what it means to be a black artist. Before I thought ‘I’ve got to make work for everyone and talk about black women, and deconstruct what black women are and are not’, but now, I think I need to be specific in my own experience, because that will add to the spectrum of our voices. The mental health conversation probably will never end for me because it’s my personal experience. Also, I think so many things affect our mental health, more than ever. The past year has been pretty strange for everybody I know. So, how images affect our mental health, from the spectrum of negative to positive, and in all ways , even entertainment, I think that’s what I’m really interested in more than anything. Also agency. What does agency look like? If you can’t separate yourself from the white gaze, ever, what do you do? How do you respond? Where do you find your power? How do you get that back? Also, power can look like vulnerability and someone being in pain and sad. Power can look like anything. I’m interested in all of that variation. My work’s moving towards performance art. I’m aiming to create my first performance art piece this year, so I feel my work will change depending on what I want to say. That sounds so pretentious (laughs), but that’s the truth.

P- What does it mean for you to photograph the black body? Or does it not even cross your mind?

H- Well, it’s that thing, that everything we do is political. Everything. So, before I thought ‘I don’t want that’, but now I think, ‘Okay, if that’s what that means, then how could I subvert that?’ There’s a power in that. If everything you do, or everything I do means this massive thing, then how can I kind of exploit that or experiment with that dynamic of power? I don’t ask myself those questions. Maybe after those images are made, but not whilst I’m making them, else I'd feel as if I’m trying to make a statement about black people in general, which I don’t really want to do.

P- How does your work operate as a healing space?

H- I think in the work, I’m trying to explore different versions of myself which for a long time, I felt maybe a bit of shame about. A lot of it was about pleasing other people’s expectations . Because I’m an actor, I consume so much television and film, and those depictions of black women did something to me, it really did. How I saw myself, how I communicated with different people. I’m an excellent code switcher. Quite scary sometimes actually, depending on where I am. I just totally change, and I think, ‘what is all of that?’ I think that thing of growing up and feeling like you have to be like this. You’re from South London, you’re from this socio-economic background, and people get confused when you talk to them. You make this work, but you talk very informally, so, I’m trying to deconstruct myself really, because this pushing down of who I am has caused me some mental health issues. I needed to just strip away those layers. All of us do.

The generation before me, my mum’s generation, they didn’t have the space to do that. Before I resented it, but now I’m like, ‘I understand why you did that. It wasn’t safe for you to do that, like definitely don’t do that!’. I totally get it. But now with what my mum and her generation have done, I’m now like, this is the time, lets expose this stuff. This is what’s going on. So, my work always lives in this vulnerable space. And during the making of the work, it is quite heavy. There is something about looking back. I feel like healing, especially for me, is a self-awareness when you just see everything clearly, and things aren’t controlling you that you can’t see, it’s not in the subconscious. You can see it. Something shifts. So, the work is like, ‘this is me’, and it gives me a sense of clarity. And the people who interact with my work often say that. Like, you’re really brave, and I’m like ‘not really, I’m just being honest!’ You probably have these same feelings about this. So yeah, I think it’s like a mixture of catharsis and just like, exposure and vulnerability. That’s where the healing is for me.

P- How do you hope the series will impact viewers?

H- Gosh…I don’t know. It’s funny. There was an online exhibition of the work two weeks before George Floyd, and then ever since then, I was inundated with interviews, and you know, this has been happening before George Floyd. In terms of black artists feeling like they’re in hostile spaces, and having to kind of contort themselves and not feeling safe, that’s been happening long before. I hope that that conversation continues, and I hope my work enables that conversation to continue in a more genuine, real-world way where people aren’t just saying that we're doing anti-black work or these policies.

I think I’m interested in legacy. If this affects artists after me, then I want that sort of real change to happen. When I’m thinking about what specifically, not just tokenistic. I guess I want people to re-address their collections. Not just ‘Heather, we want you in our collection because we're having a think about black work in our collection’, but really, ‘What are you trying to say with this?’ I feel, for me as an artist, I’m also being way more defiant. I have these collections, and people will say ‘Heather I want to buy your work’ and I think ‘Why’? (laughs). A year ago, I would’ve said ‘Yes, definitely, yes. Take the work!’ and now I’m thinking ‘Why? What are you doing with the work? Where is it going? Do you understand what the work is? You haven’t even pronounced Aida’s name properly’ or, ‘Do you even know what I’m talking about?’. So I understand there is power in our stories and our art work, and it's not just about aesthetics. There is a wider significance. It’s really just to empower other artists. I’m doing way more interviews about that conversation, because it happens in secret sometimes, and I just don’t want that.

P- Why Photo Fringe?

H- I think it might have been because of judges like Mariama Attah. I really respected their opinions. I think that was my initial draw to the OPEN20 competition. I just wanted their feedback! You’re often working by yourself, and you’re thinking ‘I hope this makes sense. Does this make sense?’. I know Photo Fringe has always been quite experimental with how they present work. Not just like ‘here’s this 2-d image’. It felt like there were conversations happening. It’s a very enriched festival to be a part of and that’s what drew me in. They wrote an anti-racism statement. It just felt like they’re trying to do something. It’s not just talk.

Heather Agyepong is a visual artist, performer/actor and maker who lives and works in London. Agyepong's art practice is concerned with mental health and wellbeing, invisibility, the diaspora and the archive. She uses both lens-based practices and performance with an aim to culminate a cathartic experience for both herself and the viewer.

Heather has been nominated for Prix Pictet & Paul Huf Award in 2016 & 2018. Her work exists in collections including Autograph ABP, Hyman Collection, New Orleans Museum of Art and Mead Art Museum. Also, nominated for the South Bank Sky Arts Breakthrough Award 2018; the Firecracker Photographic Grant 2020 and recently selected for FOAM TALENT 2021.

Pelumi Odubanjo is a freelance London-based multidisciplinary artist, writer, and curator. Having recently completed her MA in Contemporary Art Theory at Goldsmith’s, University of London, her current work is centred around archival imagery which explore black liberatory practices, and is informed by a black feminist epistemology. Her most recent awards and projects include receiving the Forshaw Fine Art Endowment Award (2019), curating for the Tate Exchange at Tate Modern, producing for Stance Podcasts, co-founding the art research collective Contakt Collective, and being the selected curator-in-residence with the Black Cultural Archives (2020).

Our relationships to historical images and vernaculars form a crucial medium for Pelumi as a photographer, researcher, and artist, with her practice exploring and reflecting upon the intersectionality of women, migration and black identity with means to unravel our understandings of archival practice.