Interview with Samuel Fordham - C-R92/BY

Flynn McDonnell, one of the three selected Photo Fringe 2020 Trainee Curators, interviewed Samuel Fordham shortly after the festival to find out more about this exceptional and timely body of work.

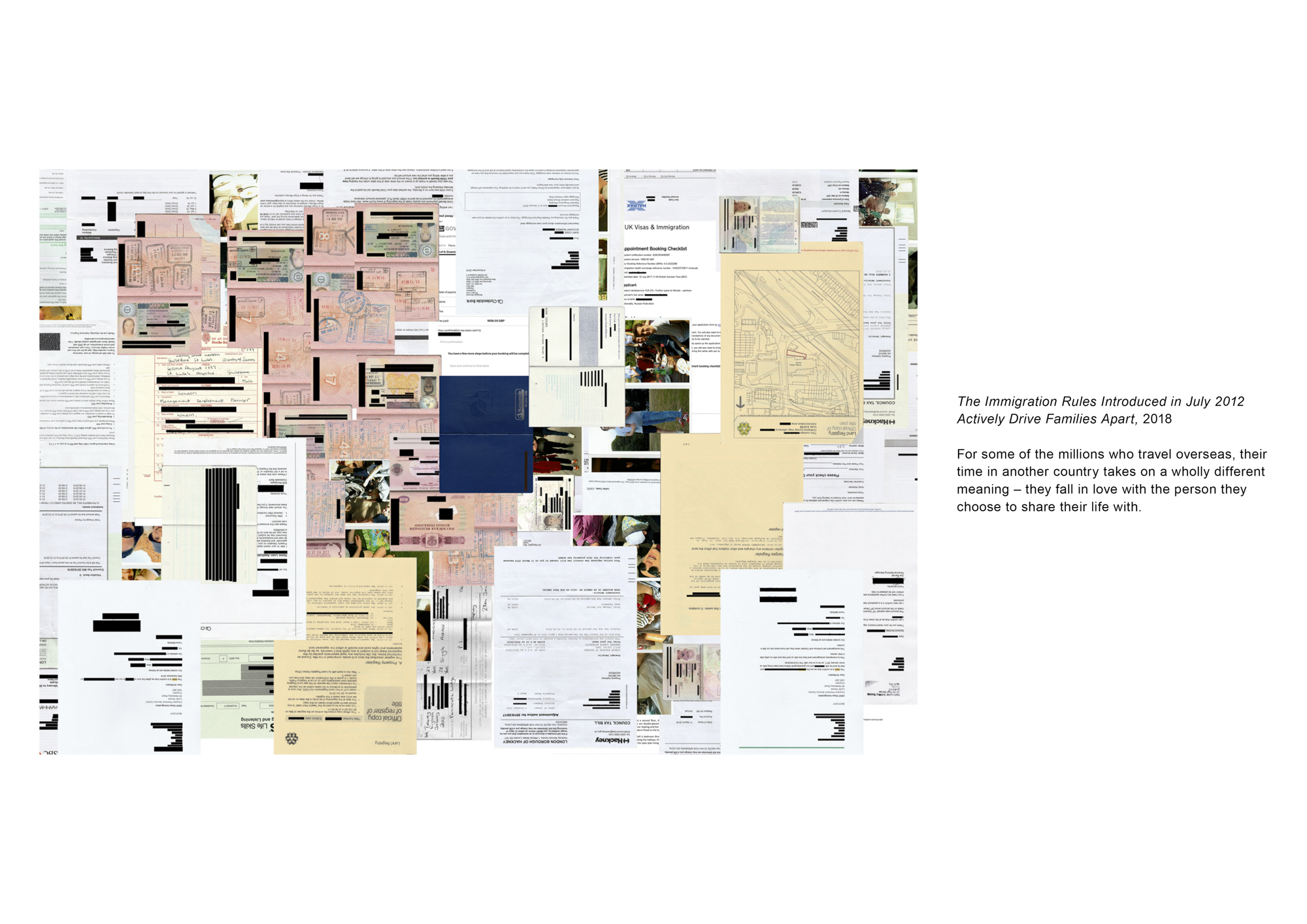

Following several decades of anti-immigration politics by the UK Government, the Minimum Income Requirement was introduced as a means to ensure migrants would not become a ‘burden on the state’. Yet, despite having been subject to legal challenges in the supreme court and condemned by migrants’ rights groups and family campaigners such as the children’s commissioner Anne Longfield, the legislation has ultimately led to the separation of around 20,000 British families. Both cruel and unjust, the legal criteria require UK citizens to earn more than £18,600 before they can bring over a non-EU partner or spouse - rising to £22,400 if they have a child who does not have British citizenship; a threshold that over 40% of the population cannot reach.

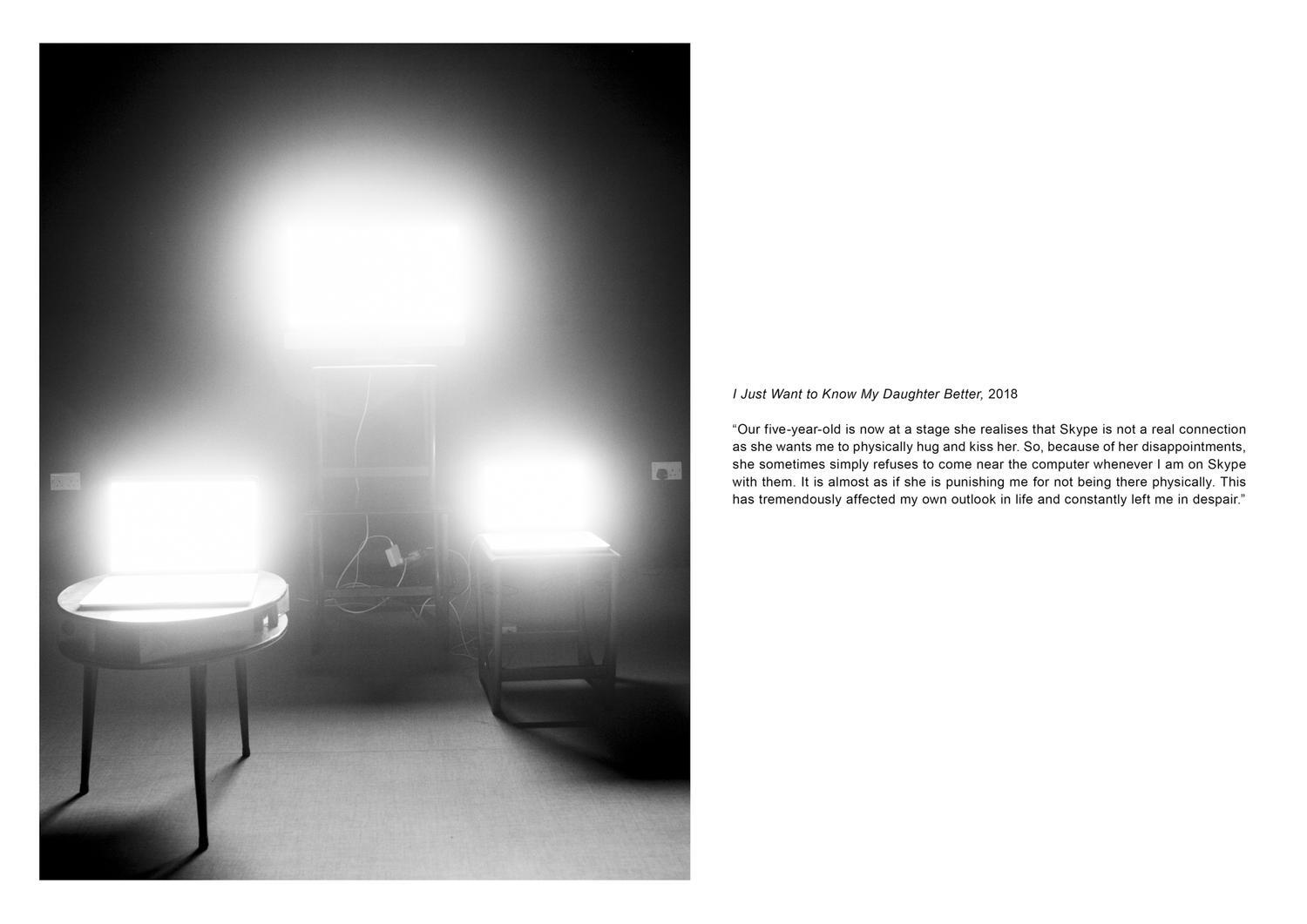

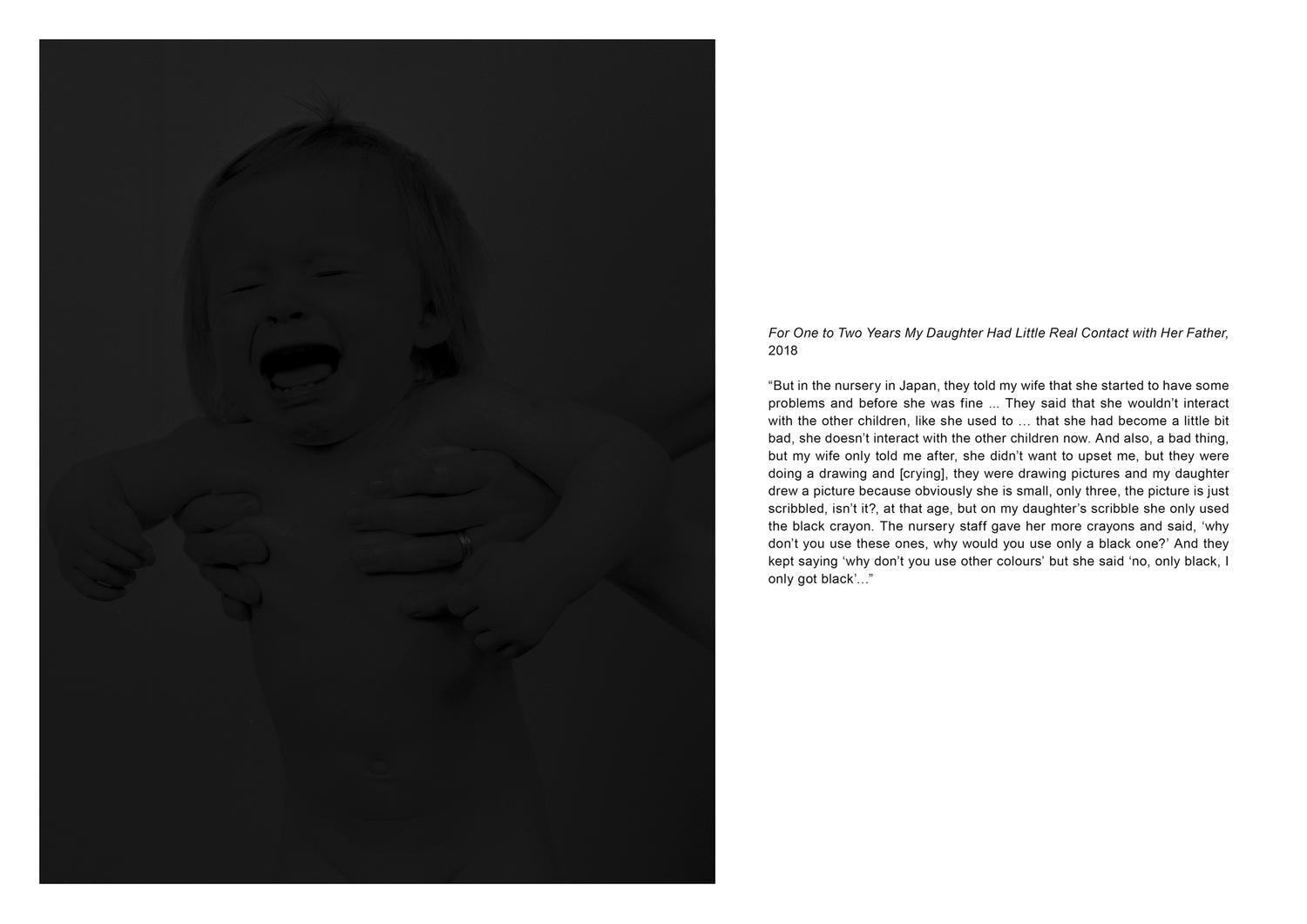

Actively driving families apart, this policy has resulted in many children suffering the stress and anxiety caused by the separation of their parents. Recent research published by Bail for Immigration Detainees (BIDUK) has further demonstrated the short and long-term effects of detention and deportation on children and families, as they experience disadvantages across a variety of behavioural, educational and health outcomes causing deep and lasting psychological effects. Having to rely solely on technology to stay connected with their stranded parent overseas, has led to the rise of what are now being referred to as ‘Skype Families’.

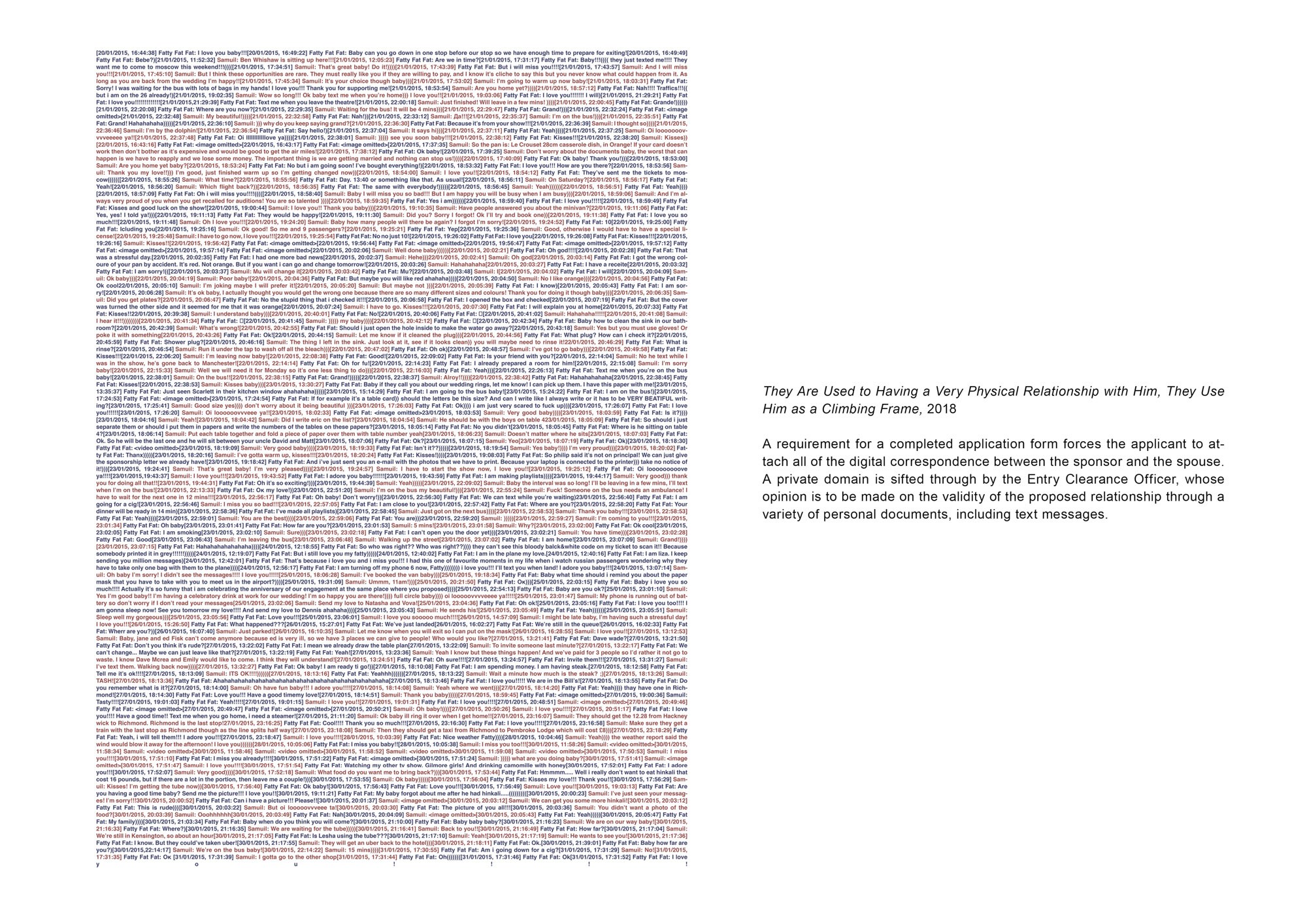

In January 2021 the Government’s post-Brexit immigration plans have become a mix of salary thresholds with a clear determination to stop those deemed ‘low-skilled’ (a phrase made all the more arbitrary by the pandemic) coming to the UK. Building on an already unfair and discriminatory system, these new rules will soon not only apply to non-EU migrants, but all their EU counterparts as well, leading to the likely separation of even more families in the future. Investigating what it takes to maintain a relationship with a family member who has been both physically and geographically removed from one’s life, ‘C-R92/BY’ explores the UK Government’s most divisive family immigration policies, as it seeks to question what it means to ‘take the irrefutably unique and transfer it into the infinitely replicable’.

For all the toxic discourse of defending our borders from outsiders and endless tales of immigration bringing problems to the UK, too few debates are as concerned with just how difficult it can be to migrate to Britain. Interweaving the stories of families battling the hardships of detention and separation, with the personal experience of his wife facing potential deportation, artist Samuel Fordham’s series switches between various visual formats to understand what it is to love someone through a two-dimensional image, while questioning what dangers can arise through such forms of representation.

Each of Fordham’s images is intrinsically unique in its visual aesthetic and style as the project mixes photographs and digital montages with official and archival documents. Working alongside the activist organisation Reunite Families UK, Fordham draws inspiration from a variety of creative processes as he strings together the testimonies of the impacted families. ‘C-R92/BY’ is a deeply emotive and personal photographic project, as critically aware of its role as a visual medium as it is concerned with the socio-political issues at play.

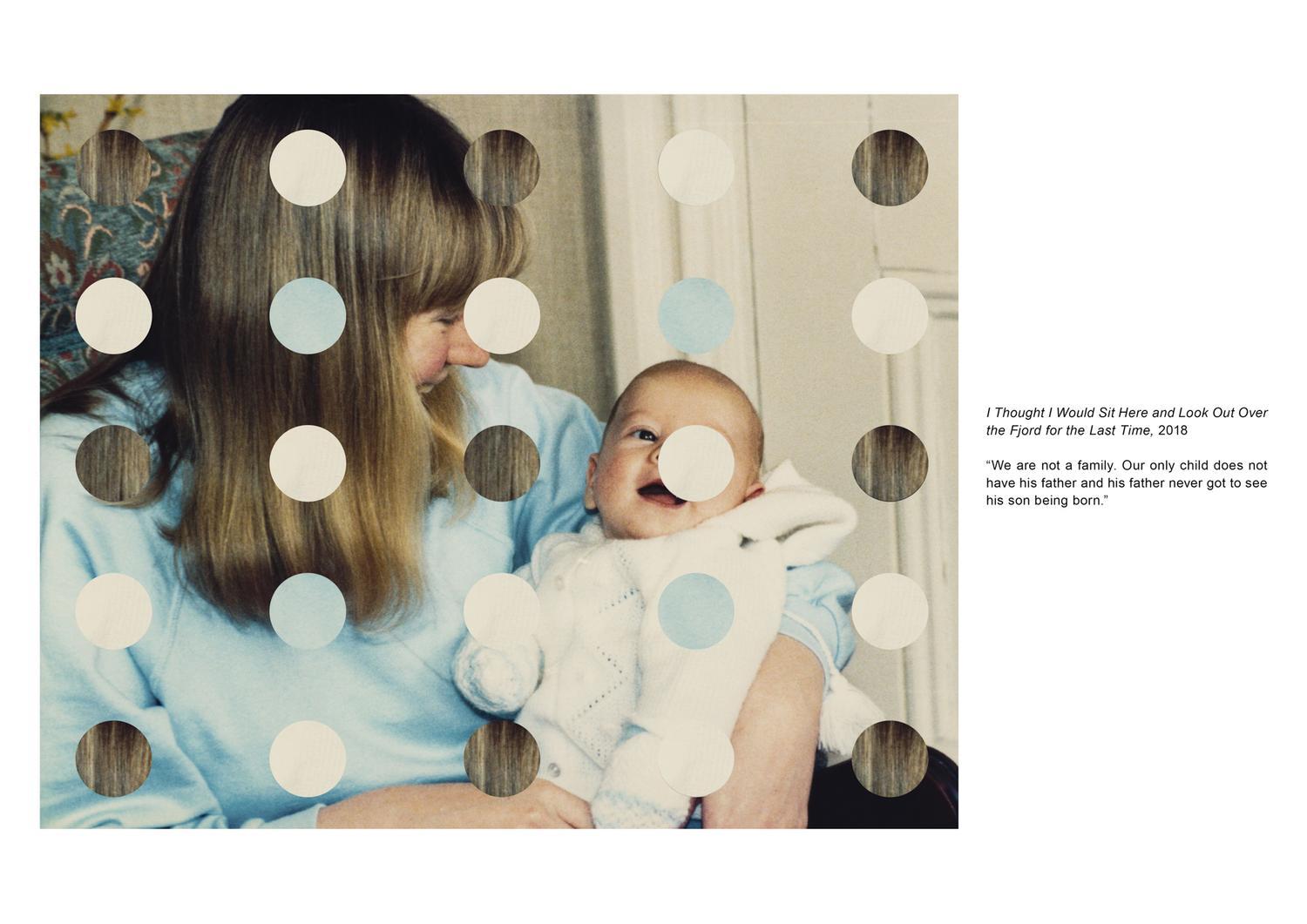

Exemplified most effectively in ‘I Thought I Would Sit Here and Look Out Over the Fjord for the Last Time, 2018’, Fordham distances the viewer from the work by drawing attention to the visual mechanics of the image itself. Inspired by his own background in theatre, Fordham draws on German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s notion of ‘Verfremdung’ – the process of making the familiar strange. Central to this idea is the notion of alienation, a theme Fordham conveys through the visual manipulation of a traditional family photograph. Overlaying a snapshot of his Visa application form, marking the places where he had inputted data, before removing all traces of the Visa altogether, Fordham builds a barrier between the viewer and the image. “This is a moment of alienation”, he explains, “the illusion has been broken and the mechanics of photography are moved to the foreground, not the illusory state… The manipulations are there to break the illusion, to foreground artifice and draw attention to the surface and material properties of the image, in the same way that Brecht would have actors changing costumes on stage and reading from scripts. It is all theatre”.

By dismantling and highlighting this artificial nature of photography, the viewer is forced to find a new understanding of the image, moving beyond its commonly associated relationship in order to form a new one. As Fordham further suggests, “I was trying to communicate the use of photography within a family unit and how, when your family is taken away from you, the surface of the photograph moves from being a window into a memory of your life together, and instead turns into a wall, a reminder of the divide”. A feeling perhaps many of us have come to realise more over the course of this pandemic.

Going into lockdown in March 2020, it was hard for many to escape the initial sense of novelty; as virtual quizzes and family Zoom calls became common activities for households all around the country. However, as the pandemic draws on and the novelty of lockdown has given way into fatigue, all many of us want is nothing more than to just safely spend time with our loved ones once again. Not only has the pandemic highlighted how much of a mediator technology has become to our physical relationships, but it has also revealed how superficial such forms of communication can be. COVID-19 has illustrated how separation increases our sense of loneliness and its detrimental impact on mental health. Fordham’s project will resonate with many, reflecting as it does the same sense of pain and isolation that many of us have had to experience this past year.

Since the early 1990s, estimates suggest there has been, on average, a piece of legislation on immigration every other year. All leading to ever-tightened and more-complexed immigration controls. Politicians will claim immigration is a taboo subject, yet this hasn’t stopped it from becoming a central topic of the political conversation; and while the UK Government have openly extolled the virtues of family life, this hasn’t deterred them from implementing immigration policies that actively keep families apart. Despite endless studies confirming that immigration is neither damaging our economy nor putting a strain on our public services, misconstrued facts and myths continue to shape the mainstream argument that migrants are to blame for the UK’s ills. Indeed, one of the most damaging consequences of the Minimum Income Requirement is that it enforces these very narratives; that someone’s right to live and work in the UK should be based on their ‘economic contribution’. Promoting this false distinction between those who are ‘active and hardworking’, against those who are ‘lazy and undeserving’, only reproduces this ‘good’ vs. ‘bad’ migrant divide. Certain groups will still be dehumanised, and anti-migrant politics will still be normalised, driving rationale for a points-based systems and work related visa regimes ever-further.

While the immigration debate was toxic long before the EU referendum, it is without question that such reinforced language and anti-immigrant feeling helped produce the Brexit vote. As Satbir Singh – chief executive of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants – concludes; “In building a hostile environment for them, the government only makes the world a colder and more hostile place for all of us”. But while ‘getting tough’ on migration rhetoric is wilfully cruel and entrenched, it can still be beaten by learning the lessons of the past, battling the immediate actions of the state and constructing a more sympathetic narrative for everyone.

‘C-R92/BY’ is undoubtedly a beautiful and haunting body of work highlighting the strength and resilience of families as they fight to stay together, while giving stark warning to the cruelty of the UK’s immigration system. It exemplifies the powerful role of photography as a tool for addressing important socio-political issues and creating collective change.

Samuel Fordham (Bristol, 1987) is a multidisciplinary artist working with photography, text, video and sound. A graduate of the MA Photography programme at UWE Bristol, Samuel has developed a research-based practice focused on telling intimate and often hidden stories highlighting issues surrounding childhood, family welfare and equality.

In 2018 he enrolled on a one-year mentorship through ISSP Latvia with Gordon MacDonald and Clare Strand (MacDonaldStrand), where he continued to develop his latest work C-R92BY.

Fordham’s projects are produced across platforms as installations, books and films.

Flynn McDonnell

Flynn McDonnell is a Brighton-based photographic artist and writer. Having developed a practice of traditional social-documentary photography, image appropriation and sculptural still image throughout his studies, he graduated in 2020 with a First-Class Honours in Photography BA(Hons) from University of Brighton. Particularly interested in how collaborative relationships between creativity and community can promote inclusion and diversity, his research focuses on how creative practices can be used to engage and educate groups and individuals on local and global challenges in order to help promote public debate and wider participation.

Centring specially on both past and current socio-economic policies, his undergraduate dissertation explored how artists and photographers have responded to the UK’s housing crisis, examining the demonisation of social housing and its effects on working class communities and children's early-development in London. Outside of his academic studies, Flynn is also a DJ, event’s organiser and founding-member of The Condiment Collective – a multi-platform collective celebrating music, art and culture.