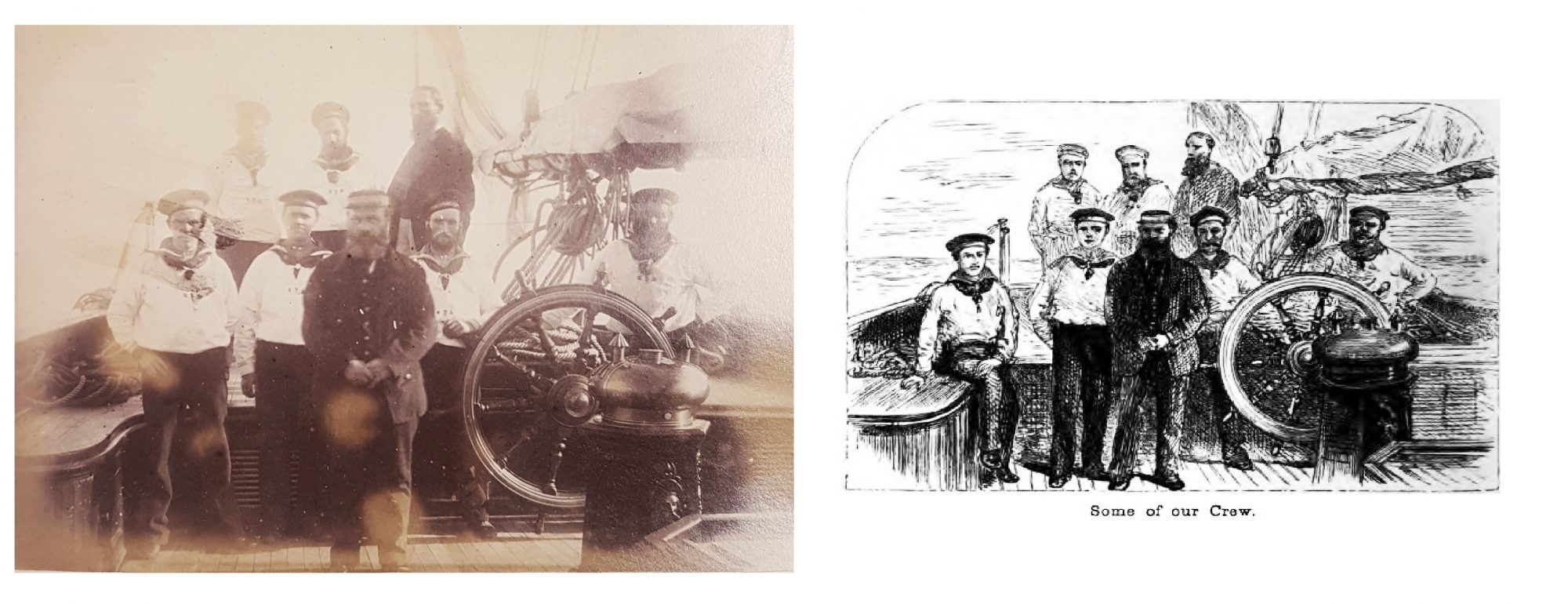

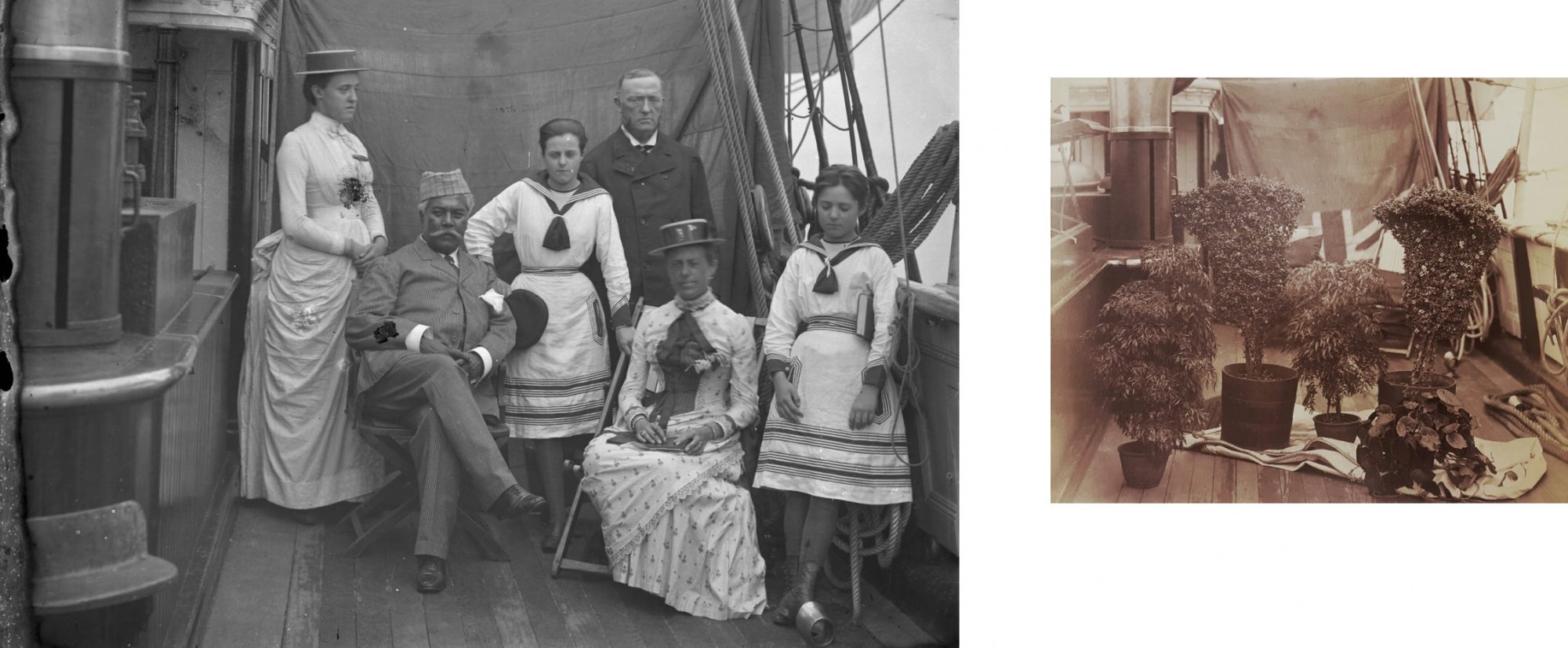

Doings of the Sunbeam: Photographs of a Victorian Voyage, Annie Brassey

Curated by Sarah French

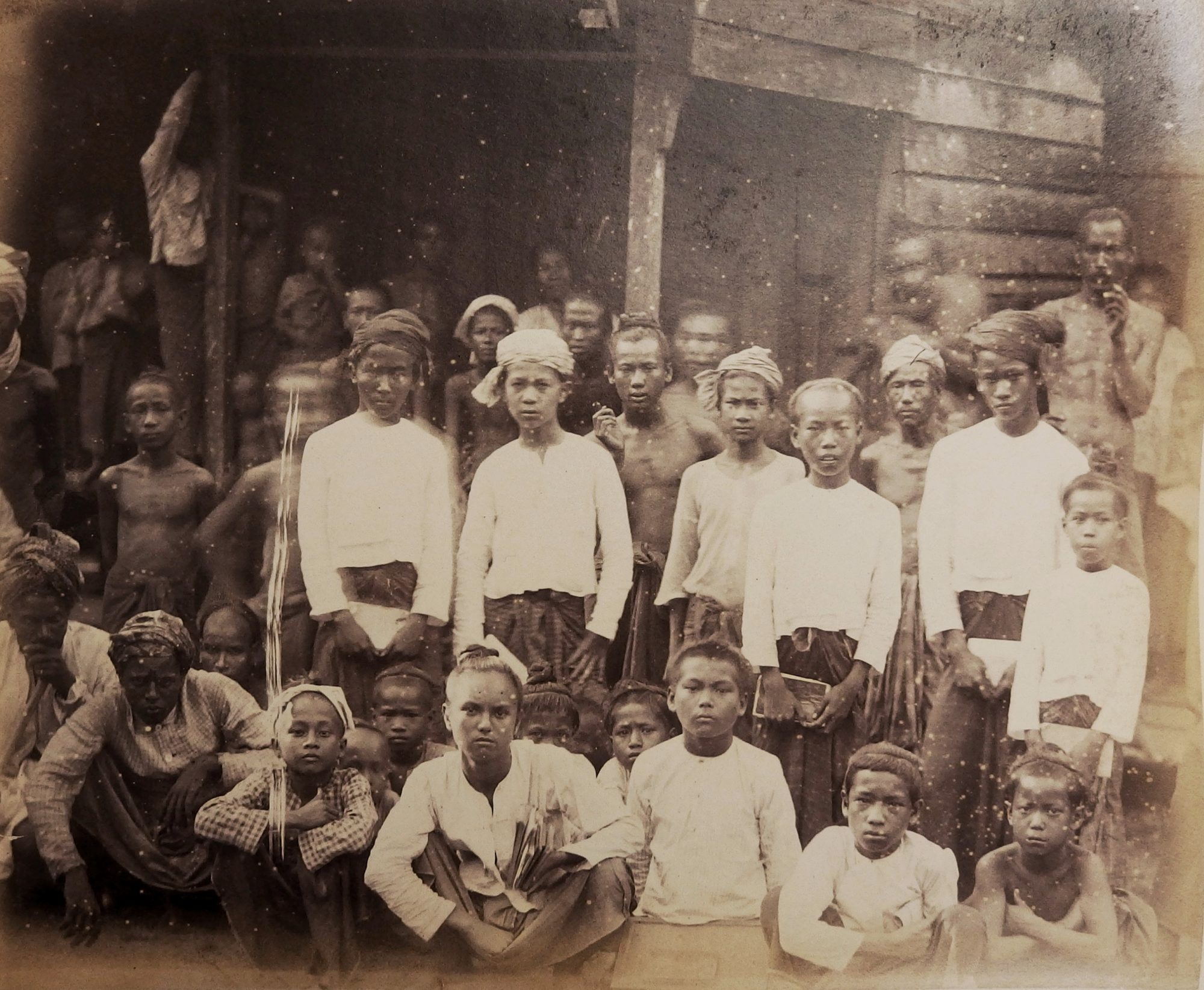

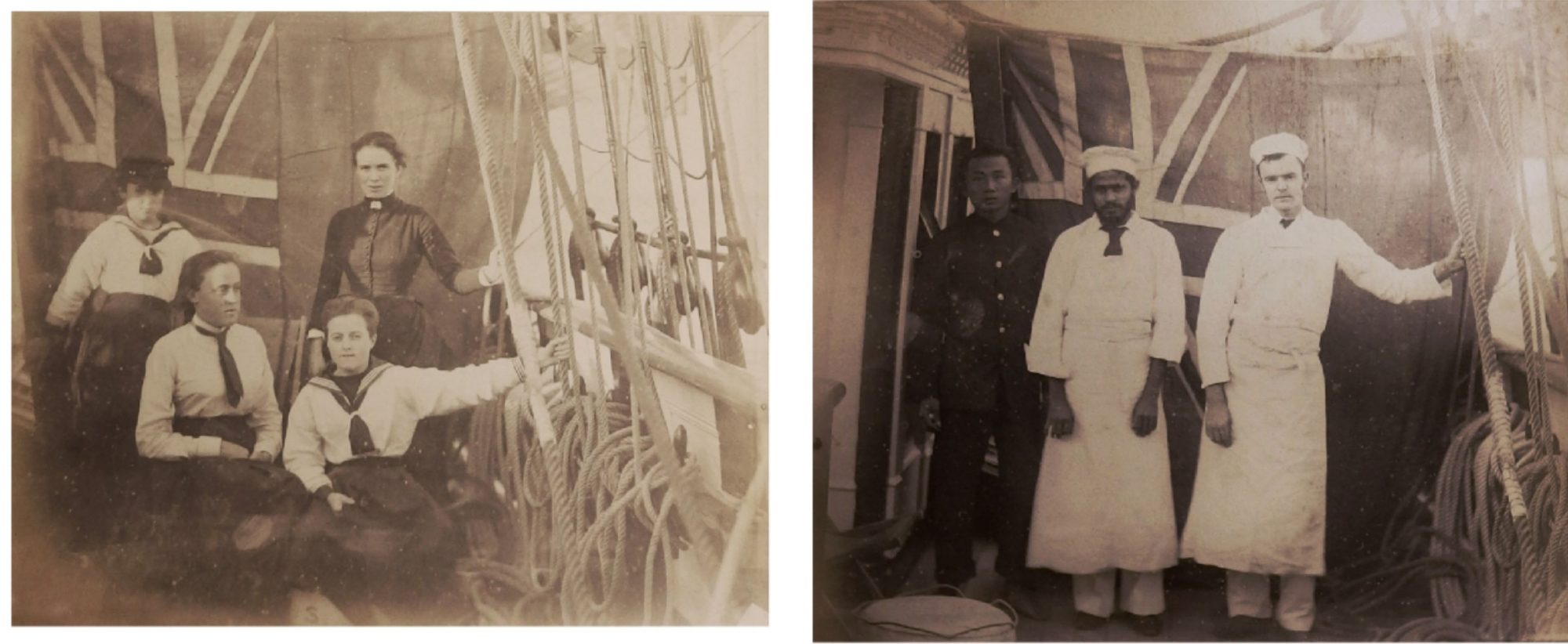

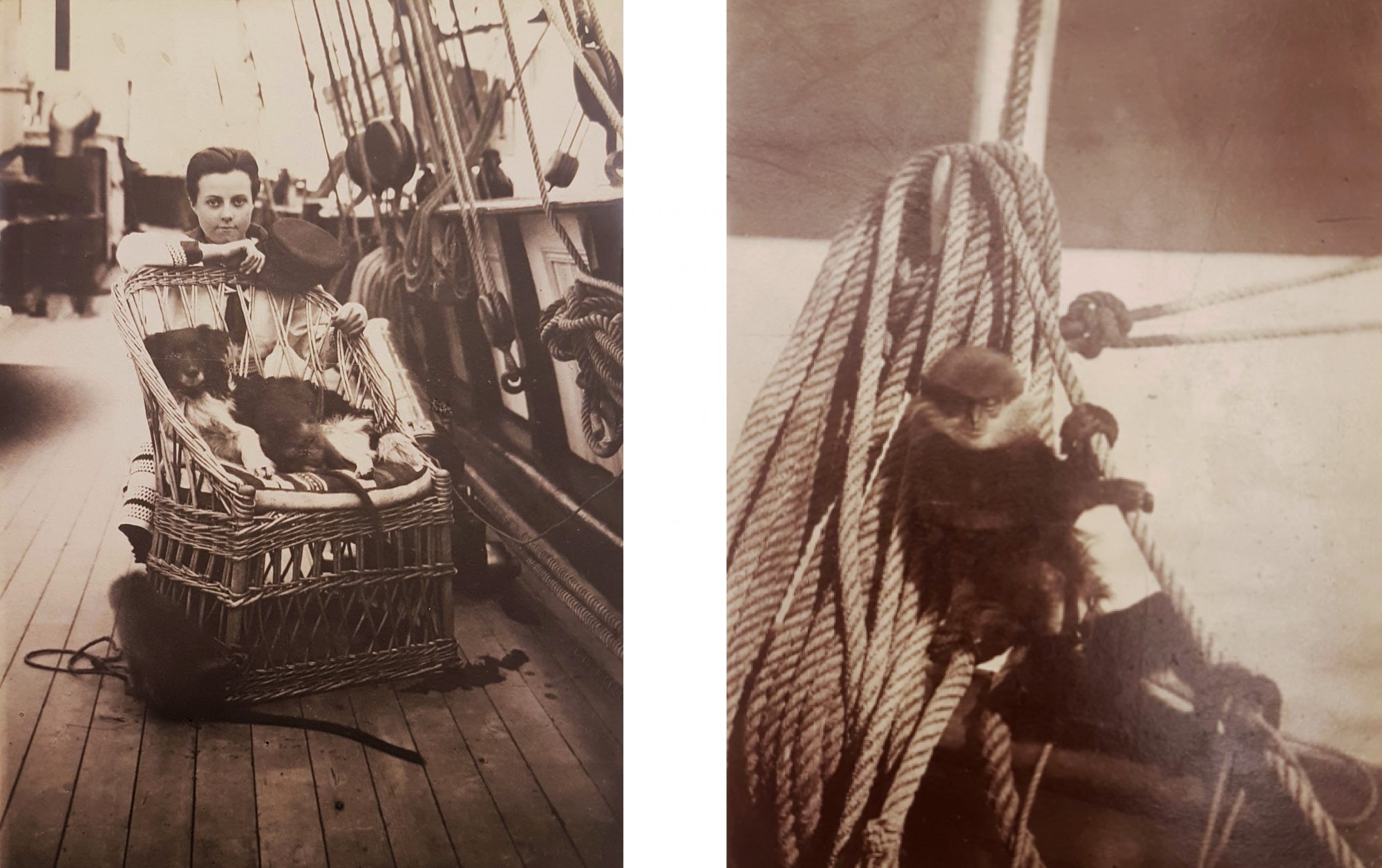

Annie Brassey (1839-1887) was a Victorian travel writer and collector, famed for her family's adventures around the world in their yacht, R.Y.S. Sunbeam. Like many middle and upper-class women of her era, she was also a keen collector and practitioner of photography. Normally tucked away in albums that are now carefully stored in archives, this online exhibition presents some of the amateur photographs taken during Annie Brassey's voyages in the 1870's and 1880's.

Artist biography

This exhibition has been produced by Sarah French, a CHASE-funded PhD Researcher at the University of Sussex and Hastings Museum & Art Gallery. Her thesis reintroduces Annie Brassey's photograph collections with her museum artefacts, re-contextualising the collections that are ingrained within the histories of British Empire.