Interview with Pryzma Collective - Nothing and Everything Happened

Pryzma Collective is a group of four visual artists who met as University of Brighton MA Photography students; Amanda Gordon, Zara Pears, Ola Teper and David West.

During the de-installation of their October 2020 Photo Fringe exhibition Nothing and Everything Happened at The Regency Town House in Brighton, Ezra Evans chatted to them about their show, the impact of Covid19 on their practice and about working in a collective.

Ezra Evans:

Let’s start with you Amanda. Can you talk about the works you exhibited?

Amanda Gordon:

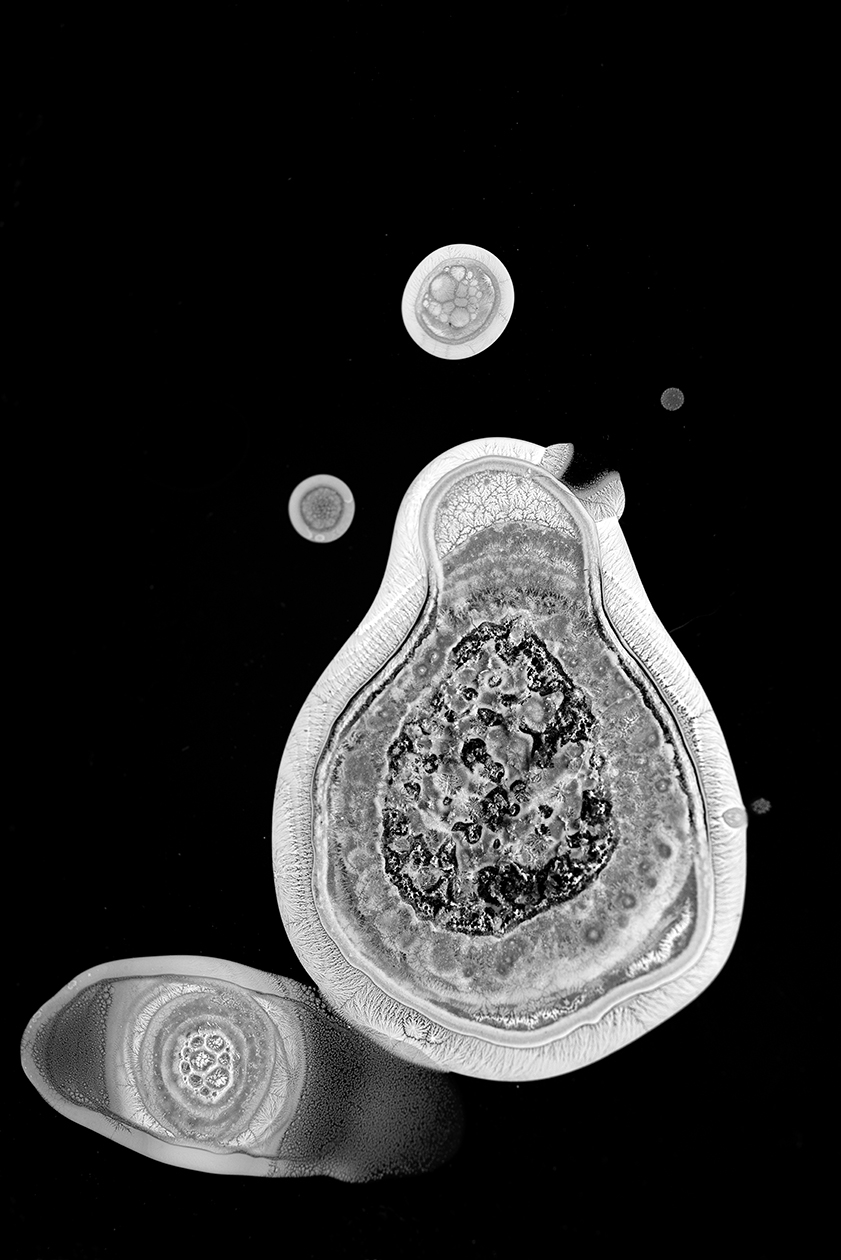

I showed a sculptural piece, made of reflective aluminium, which was two metres long and then shortened to a metre. In the same way that our social distancing rules were shortened from two metres to one metre. The idea being that when the show ended, the aluminium would be swabbed and the samples would then be cultured in petri dishes. I will then photograph whatever grows and make a grid of photographs that will be presented, with the sculpture, in a body of work in the future.

The work on the wall was of spit and soap. At the time, the government were talking a lot about aerosols (particles in the air) being released as people breathe and speak. As you're walking down the street, you’re breathing in other people’s aerosols. I think we are all aware now of the abjectness and the fragility of our bodies, due to this. Although the project wasn't directly about COVID, it relates to the boundaries of our bodies and what happens when those boundaries are crossed.

Washing my hands created some of the byproducts to make the images. I placed these byproducts of myself (the spit) and dirty soap on a digital negative (acetate) — a clear material — with one smooth and one rough printable side. You can use these in the darkroom, as a negative but instead of exposing them to light or ink, I spat and dripped soap on them directly. After leaving them to dry for 24 hours, I used a macro lens to isolate all the different areas that were visually interesting. The soap and spit actually started eating into the emulsion creating these small lines and veins within it and resulted in the images.

Ezra:

I've noticed you referencing 'the abject'.

Amanda:

There’s quite a few Julia Kristeva references in there.

Ezra:

Her definition of abjection seems central to the work. Are you able to expand on what abjection is for those people who haven't heard of it before? The text itself is interesting. I remember it feeling quite Gothic.

Amanda:

Powers of Horror?

Ezra:

Yeah.

Amanda:

The text is really dense. Rina Arya, a professor at Wolverhampton University, deciphers Kristeva and puts the works into a more contemporary context, making the text a lot more understandable. At the moment, due to COVID-19, our whole lives are filled with this abject. It's not really a feeling, it's not an emotion, it's a combination of factors — the threat and fear of contamination. COVID basically sums up that abject mood in which we are living, that potential threat to the boundaries of ourselves.

Ezra:

The pictures themselves, are they images of the bacteria on the film sheet? Or were you saying the soap or the bacteria were eating away at the emulsion of the digital negative and that is the picture?

Amanda:

I don't think it was the bacteria actually eating the emulsion. It's more that the saliva and drips of used soap suds have started spreading out as they dried. During the drying process instead of just evaporating, they started spreading out within the acetate itself and creating these small veins, like streams or rivers.

They looked organic and otherly (not immediately identifiable). For example, if I was to take a photograph of David it would be a likeness to him, an indexical image of him. When you’re photographing things like this, they become quite abstract and unidentifiable.

Ezra:

In a sense, it's still a record, like a portrait, just of someone's saliva rather than their face. On a microscopic level, all the same stuff is there, so you could consider it a portrait. They look quite medical or scientific

Amanda:

A lot of people who saw the photos thought they were microscopic images, but they were just macro images. They have that medical, space or underwater look; a sort of investigational aesthetic. They didn't look like anything of this world. They looked like something that is normally not visible to the naked eye. The idea that these samples of my saliva and the soap I had used to wash my hands may contain a contaminant, and if it did, what would it look like?

David West:

If I could just add — in those very early days when you didn't know if you had been exposed to the virus, it may well have been the virus trapped within the matrix of the trace that was left.

Amanda:

I started making this work before wide-scale testing was available. During this time one of my children and my partner had symptoms so, we all had to self-isolate for two weeks. Both of them had coughs and fever and I did consider the potential of a trace of the virus actually being on the acetate surface. However, I was making something physical and photographic out of this situation, a situation of fear that we all found ourselves in.

Everyone has become increasingly aware of the fragility of their body. Whilst walking down the street, people avoid you and you would also avoid them. In any good horror film, you know who the bad guy is, who the ‘other’ is. In this scenario, you were potentially the other, you were the one who could contaminate them. In the initial stages of this project, that was very much in my head, that I could potentially cause the death of someone.

Ezra:

It really comes across in the work, the otherness of the virus; the virus as something that's out to get you. The body, the saliva and the contaminant are all working against each other. It’s interesting to put a physical, visual spin on that, as at that time in the early days of the virus, no one had a clue of what it might look like or even what it was.

Amanda:

That harks to Kristeva's writing on the matter, and then horror films, there is always the ‘other’ who's isolated from others, but has this potential to do harm.

Ezra:

That relates to your reflective sculpture as well doesn't it? The ‘looking back at yourself’ or the ‘other you’, the reflection of you.

Amanda:

This was also created by the distortion of the reflected imagery, upon the slightly concaved surface, when viewed from certain angles. When standing above the mirrored surface, looking down, you could not see yourself in the reflection. Instead, you would see other people looking at it or people walking past or gazing into it. I think it’s also about other people watching you.

Ezra:

There's an element of paranoia to the mirror, the idea of seeing a blurry figure behind you. Also, the now instilled fear which everybody has of anybody being within a metre of another person.

Amanda:

With any sculpture on this floor space, people tend to give it a wide berth. There's something about being in a gallery space — if there’s something on the floor, people tend to give it that space without being instructed. People do distance themselves without really thinking about it.

David:

It's always a pleasure to invigilate, watching people react to work in the gallery and watching people move. It was particularly interesting to watch people stop, interrogate and try to make sense of what the sculpture was about. Of course, it was very, very fragile. It’s ultimately two carefully balanced metal sheets. People did give it a huge amount of respect; there was a lot of navigation and a lot of space created around it.

Ezra:

Yeah, I think that's one of the things that tie all the works together — the activity of trying to work things out. Nothing in the exhibition was simply given to the viewer on a platter. There’s an element of curiosity in your work and there was an element of trying to work the piece out when I looked at it. Ola's work is similar to Amanda’s in this regard. You had the images on the wall, which invite you to puzzle all these different parts of the work together. With the pictures of the eyes, we're aware there's something alluding to seeing and how one perceives things. There's still a lot to get through and a lot to try and work out when you look at the work.

Ola Teper:

My piece was supposed to be a continuation of my inquiry into trauma and PTSD. I've previously been trying to find out how photographic processes and prints can act as an allegory. I've been reading about trauma and some texts by Freud. The first moment when he realised that people are not just driven by the pleasure principle, but they are also driven by fear and trauma in their lives and the decisions that they make subconsciously. He compared it to the photographic apparatus and this idea of latency.

For instance, if someone is exposed to something that is too painful the subconscious can repress this and a latent memory can remain dormant until it later manifests as trauma. The exposure generally happens as a child or adolescent. I thought it was quite interesting to put those two things together (photography and trauma).

When Freud was writing, the general consensus on photography was that it was not representational. At the time people still considered photographs as having their own agency. I've read a bit more of Margaret Iversen and Ulrich Bae, who elaborate on the idea of photography as a metaphor of trauma. The language used in photography and the research of trauma are very similar, for example, the words 'development' and 'exposure' are prominent in both.

Ulrich Bae wrote a really brilliant essay, about the flash and the shock of the flash and even about the use of the flash in early experiments by Jean-Martin Charcot who invented hysteria. In his studio, the flash became the element to create shock. I became interested in how the photographic light is an element as well. And how photography in this sense was crucial to developing a sense of history. He was able to diagnose patients by observing their reaction to the flash, they would freeze for a few minutes and be in a state of lethargy. This is a symptom that has been discovered, only because of the use of photography, if we didn't have automatic flash, we would not be aware of it. There is a very intricate relationship between photography and trauma.

Ola:

I've also looked at EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing), which is perhaps at the core of the exploration here. EMDR is a therapy most commonly used for treating PTSD. No one quite understands why it works, but it's funded by the NHS. It's one of the most popular treatments you can get. So, it certainly is something that has positive effects. I think you had it Zara?

Zara Pears:

A close friend had a lot of success with it. After years of it she now hasn't really got PTSD, and it's completely changed her life.

Ola:

The treatment itself is quite simple. You might be familiar with an image of a physician moving his finger to hypnotise? It’s similar to this, but the difference with that treatment is that it is the patient who does the talking. Supposedly, if you move your eyes from left to right, as you talk about the triggering experiences, your mind focuses on being emotionally engaged and this triggers a flashback. After a few sessions the patient becomes able to dislocate the emotional engagement from the memory, and then they can partake in talking therapy because it is no longer triggering.

It's interesting to me, first of all, because eye movement is such a mechanical thing, it's like the body has a button that can be used to dissipate something or rewire something in your brain. It is quite a funny idea for me, because I come from Poland and it sounds like something that would be happening in 1950s experiments. The whole period of psychology after the Second World War was very focused on the mechanical actions of the body. There is an element of this in EMDR. That's why, instead of focusing on healing trauma, the work focuses on the idea that you are subjected to something through the movement of the eyes, and you don't quite know what it is because you don't know the intention.

Ola:

Coming back to the idea of the metaphor in the shared language between photography and trauma. The question is ‘what is the potential for photography’ Because photography, obviously, involves eye movement so how can the viewer become a part of that? Through my research I also looked at emission theory, where it’s believed that the eyes are actually projecting light rather than taking it in.

In the project, I was trying to find a way to build a system of correspondence between all the elements. The elements of the human eye that have been observed, the relationship of the images between themselves and the video piece as well. You have the eye, you have the lens which will be on the opposite spectrum, you have the lights which are used in the video as a trigger, they mimic a slowed down version of EMDR treatment. You also have the viewers eyes which are triggered by certain pieces to move from left to right. I think of it as a system of communication for when you become trapped. Even the two small images on the walls, where you have the traces of the eye movement and the traces of the light movement, they are treated as different entities with the same quality, the same agency.

Ezra:

When I came to the private view we spoke about the two images of the enlarger, and we spoke briefly about inherited trauma through objects that you had inherited and the baggage that you can offload. Could you reiterate what we spoke about in relation to the two images of the enlarger?

Ola:

That’s something that was not meant to be a part of the show. It wasn't meant to be a part of this work. In my practice, I always want to do work on something that is not personal and then I regret it. I promise myself I will do it but it just creeps back in. It’s like sabotage. I think this work is a good example of that. It was supposed to be about eye movement but because of COVID and having just started the practical module in my first year of university, I had to continue working. I remember that I had an enlarger in my childhood and I asked my dad to ship it to me.

Now, the reason I say that this is something that creeps back into my work, almost uninvited, is because for the last three years, I've been drawn into working with inherited objects which relate to my experience of homelessness and my fear of losing objects. Therefore, I prefer not to have too much stuff because I don't want to lose it again.

Everything that comes into my life comes in with the potential to be lost. The inherited object is an object that you're supposed to care for. It's not about the object specifically, the enlarger was in my living room after my dad shipped it to me. It interrupted all of my thought processes to a point where I thought that, if I have to do work for the module, I might as well do some work with it, if it makes me unable to work on anything else. That’s always been an element of my practice from when I started to take images more seriously.

Because of this, I’ve also become interested in what it means to ask for an object. And how this highlights the trajectories between people in your family, and people in general. My family's still alive, it's not like the object has been passed on to me.

It’s almost become like a performance for me now — of trying to find them, and then engaging with people through an object or asking them for an object. So, it's just a nice way of treating the object as a kind of highway to things that are not said. The object becomes central to something that I hope we all understand. I suppose there’s also an ontological inquiry to it, of trying to find a balance between its own qualities and the qualities that are reflected in it. And so, it’s an inquiry into whether the object exists with its own agency.

Ezra:

From what I can understand, EMDR is about working through trauma and working through issues — rather than just burying them to come up at an unexpected time later on. From what you're saying about the enlarger, there seems to be an element of trying to turn the camera onto something — trying to work through the emotions that you have attached to the enlarger and where it came from.

It's interesting, looking at the video/installation piece first, it almost brings you into this different world or different headspace that then prepares you to work your way around the images that you've made. It's interesting to think about the installation piece as something that's changing your environment or changing the way you think about or view the images before you go on to look at them.

Ola:

I feel that the elements of trauma, in a certain way, go through everybody’s work. Maybe you shared this with me? I felt that sometimes, as the spoken word piece was playing continuously throughout the show, it brought the language of photography and trauma together without specifically talking about trauma. It's viewed as the language of photography. It talks about flashes being traumatic. You could hear it in the room especially when it was quiet. It brings back the focus to the fact it’s a photographic show that can have different types of works and still explore the medium of photography as well.

Ezra:

You've got a photographic process that adds an almost paradoxical element to how we see things and how we interpret things, especially the analogue process of capturing a moment and then (the camera) re-projecting through its own lens, through its own way of seeing. It's interesting to see how you turn your camera to the process of EMDR therapy. And also to the process of how we produce these images and produce these theories, by turning the camera onto the flashes through the video piece and then onto the actual process of the hypnotism and the therapy itself.

One of the things that I think is quite prevalent through the whole exhibition is everybody's use of performance. It's all used in radically different ways. From your work (Ola), where you shipped an enlarger to this country, photographed it, then printed with the enlarger, which is a performance in itself. To your work David and to Amanda's work and to your work as well Zara.

Zara:

I come from a performance and dance background. The expressive potential of photography is particularly important to me, as is using the camera as a means of self-expression. Also, collaboration and what you can make with somebody else that you couldn't make on your own. Performance for me is a way of working through something. When I'm making the work, I'm very much in it and experiencing it in that moment. Even though I come to it with some ideas of what I want, it's a real collaboration and working-through of something. I'll know that I'm getting somewhere if I'm getting this energy.

I will often come with keywords or try to explain and create some sort of character. Sometimes I'll talk about an idea or scene, for example: 'I want you to imagine this, or I want you to think about that feeling'. Then the collaborator will respond to that. I will then respond to that in return. So, there's this dialogue going on to create the images. The work explores tension in the body. There’s also an element of trying to work through tension or trauma, and the return of a trauma in the adult body that has had a period of latency or repression. How no matter how much you try to forget something, it comes back. I was very interested in how trauma is stored in the body and how that manifests itself physically if it's unable to be released from the body. The work was really trying to explore the tension within the body and being bound, but also trying to free oneself as well.

Ezra:

The images themselves were really quite moving to look at. As we just said, there's a similar conceptual interest between your work and Ola's work and the subject matter of them. As, with everyone's work there's a strong sculptural element to your work. For example, the decision to display the images on a horizontally placed door.

Zara:

I wanted to bring an element of domestic space into the work. I became obsessed with windows that had been completely boarded up. I took some images of some places, of houses that were boarded up, also houses that had been burned. I was interested in the metaphor of the house as a body, and of something that is being repressed and unable to escape. Also, the idea of the home being a site of a traumatic event, or a place that’s supposed to be a sanctuary and how it can be the opposite of that. I've always been fascinated by the use of doors in surrealist artwork and how they are used to show the boundary between the inside and outside. In my work I’m interested in the idea of hiding and revealing what is beneath the surface, what can't be seen by other people or what is being experienced very strongly by an individual.

Ezra:

I think the two parallels of hiding and revealing are very prominent in the work on the door and also on the collage that was above the fireplace where it almost looks as if you set the shutter speed too fast in a studio and you get the shutter curtains obscuring the image.

Zara:

That's exactly what happened.

Ezra:

Was there a reason for doing this?

Zara:

It was an accident. I was making that work very early and I was interested in using twins to represent the idea of a persona that is projected and a true self that is hidden. I wanted to show the tension between those two and the tension of revealing the true self and how sometimes that can be a scary thing to do. I tried to use very subtle gestures in the body. I was also thinking about childhood and childhood trauma, so I made all of these images and then I got them back and realised my mistake.

I was really upset initially, but after thinking about it I saw how it was a perfect metaphor for a traumatic event. An event that happens so quickly, that you are unable to register that event, and how that can be shocking especially in reference to the earlier conversation about the flash. You might want to repress something bad that's happened to you through trying to forget it. Sometimes, when you remember something as an adult, you can question your memory and think, ‘did that really happen the way that I remember it?’ As a defence mechanism, you can completely replace a memory and not remember it at all. Then it begins to come back as a physical form in the body.

The funny thing is, in my work, I like to use a lot of negative space, so I like to bring in this element of pulling the subject away from any sort of reality and bringing it back into more of an internal space. Yeah, it's a blessing really.

Ezra:

One thing that is really interesting is how it shows the process of photography. It's easy to think that ideas, research or photographs just happen but actually there's a real to and fro in making the photos and working through the event. The interesting thing about taking a photo is how it gives you this opportunity to separate from yourself, or the moment, to give you another perspective on things.

Zara:

Absolutely, it's interesting how those sorts of accidents can open up a whole other area of investigation and thought in the work.

Ezra:

Do you think it's something that you would try and recreate in the future?

Zara:

Yeah, I did go back to it, but it didn’t quite work as I would have liked. I'm just happy to leave it as its own thing. It wasn't planned for, I wasn't thinking about it. When I went back and tried to do picture after picture, it didn't feel as natural.

Ezra:

And to collage them together in the frame, was that purely an aesthetic choice?

Zara:

To be honest, it was a purely aesthetic choice. I was just playing around with the images. I mean, maybe it wasn't, but I can't really remember, so it must not have been a very profound reason. I just felt like it worked. I would like to experiment with doing actual collage. Sometimes I feel that there is a real latency in some things that I do that is also reflected in the work. Often, I won’t discover, or work through, or understand the choices I've made. At that time, they don't necessarily make sense. For me, I don't know why, it just made sense. Maybe it feeds into something about the fragmentation of memory and the way we experience memory and how we are trying to piece things together.

Ezra:

Another noticeable thing is that there’s three very distinct sections to your work. There were three images towards the end that I found particularly touching, they had a real tension to them. The one with the finger and the arm and the one of the hanging drapes were both really profound.

Zara:

The second one you described was some fabric with knots, and it was being pulled to create tension. When I made those two images, I was very interested in how trauma is stored in the body. How it manifests itself physically and can have very profound physical symptoms like the blockages that can occur and the inability to get them out. At the time of making that work, I was feeling extremely frustrated. I was feeling silenced when I went to speak to a GP, it is quite personal work really. What I was interested in was this communication between patient and doctor, and the power relationship. Meaning that the person is very qualified and has a lot of power and knowledge about the body. Sometimes it can feel like you're assumed not to have as much knowledge. However, you are the one in your own body. I was trying to communicate something that is not visible, that's internal. Again, I was playing with performance. I would try and explain the various locations on my body where I was holding general pain and then get the model to act it out. That’s what the work is about.

I also wanted to think about the history of women's health, and how, going back to hysteria, in some cases woman's health is not always taken as seriously as perhaps men’s health. That often symptoms are attributed to other things. For example, a woman being treated differently for heart attacks, or the fact that we should be more educated around women's health. Have we not come as far as we could, or should?

In relation to the other image, I really love working with fabric. I was trying to create tension, using fabric to make a visual metaphor for knots in the body that are caught. The last image was of a woman coming into a window. That was going back to similar ideas of the door, the domestic space and trauma, but it was also referencing a dream space. How dreams can be a return of trauma. The feeling of this cyclical nature of dreams and sometimes being unable to escape that dream. I wanted to be ambiguous and make something that people could put their own interpretation on. There were three very different approaches under the same umbrella.

Ezra:

Did you work/collaborate with the same person?

Zara:

No, those images were not that long ago. I did start shooting with her right at the beginning though. One woman, she’s a life model and she's just really fantastic to work with. And then Amanda's children actually. And then those pictures down there I made, when we were in lockdown in my backyard with my flatmate.

Ezra:

You talk about collaboration in the performances and not just using the subjects as models. I think that really comes through in the work, particularly in the way that these different feelings or ideas that you've described to them come out through the performances/images. With the images on the door you've got quite a literal interpretation. With the images on the end, you've got a much more surreal interpretation of the things that you've spoken to the collaborators about. You've really allowed your work to be a 50/50 performance in the way that the performer is allowed to interpret what you're saying, then you capture it.

Ezra:

David, can we hear about your work?

David West:

The work was completely an extension of what I did in the MA, where I was looking at producing methods, photographically, of extending the time signal of one or many events. But importantly, within camera and within the same frame. That was an important criteria I set myself when I started the MA. I got to a certain point with that, which allowed me to finish and then it's been a continual way of me enhancing, modifying, testing and working with the camera.

It's been challenging, because the results are completely unpredictable. The technicalities of the basic scanners that the cameras use and the combinations of the cameras I use. Latterly with the older lenses I was using, mean that nothing is ever guaranteed to end up the way you intend. Quite simply, the dynamic range makes a huge difference. If things are too bright, everything is washed out, if things are too dark everything is very grainy. There is truly a golden zone where it works. I've learned to work within that, within the parameters that the apparatus has created.

When I was studying, I was fascinated by this period of photography, the first 10 to 15 years after photography was invented. The photographs that were produced and had survived after being published have this wonderful quality. Walter Benjamin discussed photographs as being full of aura, and so I spent a lot of time trying to research people who knew far more about it than I did.

If you made a picture in 1850, 1950, and then in 2015, they would all look different as a result of various things that I wanted to understand. It was of course, due to the technology available. What was more interesting is that it wasn't just the technology, it was the way that many people were confronted with a camera. It was the very first time they'd seen the camera. I've watched this young woman (Amanda's daughter) playing with a camera all morning. It's the most successful and the most democratic piece of photographic technology that we can have.

Back to 1850 and 1860. People just hadn’t seen cameras and as a result — again touching on performance — when somebody set up a camera, and you put a camera on a tripod, and you put a variety of plates in the back of it, and you cover yourself with a cloth and you focus it. It's fascinating looking at the pictures, because people didn't know whether to stand in a photograph and address the lens, or whether to look elsewhere. I'm thinking of the pictures by David Octavius Hill primarily because he made lots of images on the South Coast. These exquisite photographs, made of the Newhaven fishermen's wives. There's a lot of historical information to mine from the photograph. You can actually go back to the places they were made because there was so much depth of field in them. The look of it, the sitters — we’ve spoken a lot about things looking otherworldly.

It is a huge amount of time ago in the history of photography. I've made images using my cameras which try to recreate those elements of an aura. The only way I could do that was by making very long exposures, which is what photographers of the era made. The difference in my way of making images was the camera. I’m joining a scanner to the back of a large format camera so it's getting exquisite detail. The more you increase the resolution, the slower the scanner scans, and it's mighty hard to sit as people did in 1850-1860 in front of the camera or stand in front of the camera without taking on a deadpan look.

For me the fascination is that I can set a studio camera up with lights and I can take portraits or self-portraits as I have done for many years as a practicing photographer. But when I start to look deeply and think deeply around the images that I’m making, they do look like they are of another period. It's hugely rewarding to get that. It was even more rewarding when people were looking at the work and saying, Neptune, Charles Darwin, Shostakovich. All these people were from the past. I'm not saying I've succeeded in anything, but I took a huge amount of gratification in those comments. The drowned man was one. I've never seen the drowned man. I need to check that one, I had two people make that comment to me.

Ezra:

The really interesting thing about your work is the combination of the old and new. Some people might ask, why is he going to this much effort to take a digital photograph? Could you expand a bit as to why you've chosen to do this and how you've taken a new technology like the LED lamp and a scanner, and how you’ve engineered them to work in conjunction?

David:

Francis Hodgson said about my work when I was making it, and it was a really important comment, ‘When people walk into a gallery, one of the many things they do when they interrogate a series of images is they try to understand the technology with which the images were created’. I was able to layer different things, not necessarily to cause confusion, because I've never tried to mislead anybody, but just add more complexity to the images I was making, via technology, and this confluence of old and new. Plus, I love making things and breaking things, that’s a huge part of my practice

Ezra:

Because of your references from the magic lantern to the very dawn of the pre-cinema theatre projections, there appears to be an element of trickery in the work. I remember when I came in, I was trying to work out exactly what I was looking at. Was it working or not? The experience of your magic lantern is something that you can't really show through the internet, so if you can talk about the machinery that's involved, what it's doing and a bit more about the process.

We've spoken about the actual scanning, but maybe talk about the way that you've engineered the scanner into a camera. You're using a large format camera with bellows and a lens. Then the process of actually making these glass plate negatives, where, again you have taken every aspect of the old process and the new process, and you've mixed them at every point. So it's not just a digital photograph with an old projector, every step has a mix of the old and the new.

David:

It's a bit worrying to look at it from that perspective. I try and see every obstacle I'm presented with as an opportunity. I found that lockdown gave me the opportunity to make a body of work with the camera focused on myself. I also think I've become the best model I've ever had.

All of my practice, particularly on the MA, is research-led practice. When we first came to live in Brunswick Square (also where the Regency Townhouse is situated), I was fascinated by the number of blue plaques and went away and found out who those people were. There were a huge number of artists, musicians and luminaries in various fields that I wanted to understand. Then I thought, why was Brunswick Square built here? And how? I looked at the designers, the developers, the people who put money into the project, and understood them and then started looking a bit broader. It was when I got as far as Middle Street that I came across the work of John Rudge and William Friese Greene, who were true local heroes and pioneers of cinematography. That led me to make the grids of photographs.

Friese Greene, as part of his move from still image to moving images, made many blocks of four images studying his own movements. The way they first experienced and experimented with making end prints, dipping them in oil, making them translucent, and then projecting. That gave me the anchor to use the magic lantern. I was pretty confident that anybody in late Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian times living in a grand house like this would have probably had a wind-up HMV gramophone with a great big horn on it. In the other room would have been a magic lantern, so it sat nicely.

The lantern was strategically positioned considering how best to produce a light-free environment. This has been a huge challenge in a room that's designed to let light in. There was a natural and ergonomic flow for the visitors to come in. I saw that the visitors were obstructed from the photograph by the magic lantern. I liked the fact that people were puzzled by it, in a similar way to how people negotiated Amanda's sculpture, people would almost step around it and overlook it. I think it might have been you who said, ‘Is it just a white square’ it probably looked like that at the time.

There’s a huge risk of putting work out for the public to look at. I got my decimal point in the wrong place because I would not have realised by three o'clock the sun was brighter than ever. It worked best at night.

Ezra:

I think the fact that it couldn't be on all the time made it more reminiscent of the early theatres of the 1800-1900. The way that you had to come in and turn the light off was performative in itself.

David:

We were also provided with a gorgeous screen, it was reminiscent of the early days in medicine where people would be asked to undress behind a screen. People were in there for quite some time when we got it dark enough to look at the slides, so again, another performative element.

Ezra:

There are common themes to everyone's work that aren't obvious at first. There's definitely a theme of science and medical research, as well as performance. Then there's also the dialogue between the works that you've made and the building itself. If we could talk a bit about the importance of the building. Did you choose The Regency Townhouse as a venue specifically to suit your work? Or did it fall on your lap? What was it that made you choose a grand Georgian house?

Zara:

I think it's such a beautiful space and I had seen work here before. When I was a student, one of the first things I did when I came to London was come down to Photo Fringe about five years ago. I thought that I'd love to make some work and put it in that space one day.

David:

Ha! Well, clearly I wanted to be in a gallery that was less than 100 metres from my home. (laughs). But proximity was really helpful for setting up. They gave us access to come talk and work in here, way before we were able to hang work on the walls.

Amanda:

All of my works were made in the domestic space. I made it all on the kitchen table. Having the show in a domestic space fits with my work. I like the idea that it was not in the centre of Brighton. I think that's one of the beauties of Photo Fringe, It encourages people not just to go to the exhibitions that are on show in the centre. I remember a few years ago they were actually running coach trips to show people art work. Again it’s that idea that you're slightly out of the boundaries of Brighton; my work deals with boundaries all the time. It isn't Brighton-centric, and it's accessible to everyone.

Ola:

It’s also quite an important venue for Photo Fringe. It was one of the first decisions we made. The choice of space, how it's not just a space, how it’s also good for collaboration, not just in the show, but a welcoming space for artists to use for different purposes.

Amanda:

We were meeting a lot at David’s for the initial crits. Even just sitting in his living room you would look across at where the exhibition would be, it wasn't in some remote location. It was right next door.

Ezra:

How have you found the collective experience? What has being in a collective done for you guys? Has it influenced the work you made for the show?

David:

I think, personally, being part of this wonderful collective is why I have the motivation to make the work. I've met so many photographers, they come back, this isn't a criticism, it’s an observation, they come back for degree shows every year to the same work. They tut and scratch at the fabric of the shows, but when you ask them what they've done, they don't continue to make work.

I think if you look at the effort we've all put in individually while studying, it's such a pity not to turn it into printed work. To sit with these three highly qualified and highly competent practitioners has been a wonderful experience, despite how it was through COVID. It's been communication through zooms. So it just carried on seamlessly.

Ola:

I think the element of sharing research has been particularly prominent between my work and your work (Zara). The work is so close together because we had a lot of conversations about trauma. Whenever we stumbled upon something that might open up a new direction for the work we would share it. There are a lot of links, texts and titles that we shared with each other, which was really helpful and expansive.

Ezra:

That's one of the key things; the expansiveness of it. If you're only working by yourself, you’re always within the limits of your mental capacity and your interests. As soon as you join in with more people, all of the ideas that you have can be expanded upon.

One of the things I think people don't realise is important about university is the group critique. That's what most people miss the most when they leave. I assume it's been helpful for you guys to enable each other through a collective.

Ola:

Can I just elaborate on that? I think it's a good point to perhaps explain the name Pryzma (English translation Prism). We were brainstorming about it by looking for words that would encompass the idea that we all came from the same place, and then expanded into different places. This amplification of ideas is just one point of departure. That's exactly what a prism does to light, and obviously it's related to light which goes both ways. The idea of a collective that puts people at the same point of departure and then expands into different directions — within the same area of collaboration.

Ezra:

You can tell that you've had a lot of contact with each other through the show, there's these lines that connect everything. There's intersecting points between everybody's work in the show. Everyone has this sculptural element as well. Amanda had the mirror, and you (Ola) had your drawers and the television and your door Zara, and then David’s magic lantern. There's all these things that tie the work together.

If we could speak about the installation of the show, and working collaboratively in that respect and then also a bit of hindsight about the show? Is there a way that you wish to expand and change things? If so, how do you see the work and the collective going forward into the future?

David:

I think the walls look very bare now.

Amanda:

It's the finality, isn't it? I hate taking shows down. Just that huge energy behind getting it up there and getting people in to see the show and now it’s that deflated feeling. You either just wallow about or you think about what you are going to do next. I think the majority of us are all thinking about what we are going to do next, to keep that motivation going, but I hate this bit. I hate when you take stuff down. It seems to be the end of something

David:

Maybe that's the way you finally resolve your work. In that, it comes down, gets packed up, and maybe it doesn't come out for a couple more years.

Ezra:

That is what is important about shows — being able to finalise work. It always seemed to me that, as a photographer, especially now in the digital age, it's so easy to just make, make, make, and think and think and collect and express without any kind of resolve. I think, for all artists, to show work is an opportunity to wrap up all of those loose ends and realise that this is only the beginning of something, or maybe that it’s the end of something, and then something new comes out of it.

Ezra Evans is an artist and facilitator who has exhibited at RPS Gallery, Stills Centre for Photography and Street Level Photoworks. Ezra is a member of YumYum collective and a founding member of (re)structure group.